Scientists surprised the last world year by saying that you found out phosphine traces in the Venusian clouds. New research suggests this gas – which, interestingly, is, produced by microbes– they were not responsible for the signal they found. Instead, it seemed to be sulfur dioxide, a less good chemical.

Special research published in Nature last September was challenged by a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal, the introduction of which is currently available at the arXiv. This is not the first paper to criticism Venus appears to have phosphine, and this does not appear to be the last.

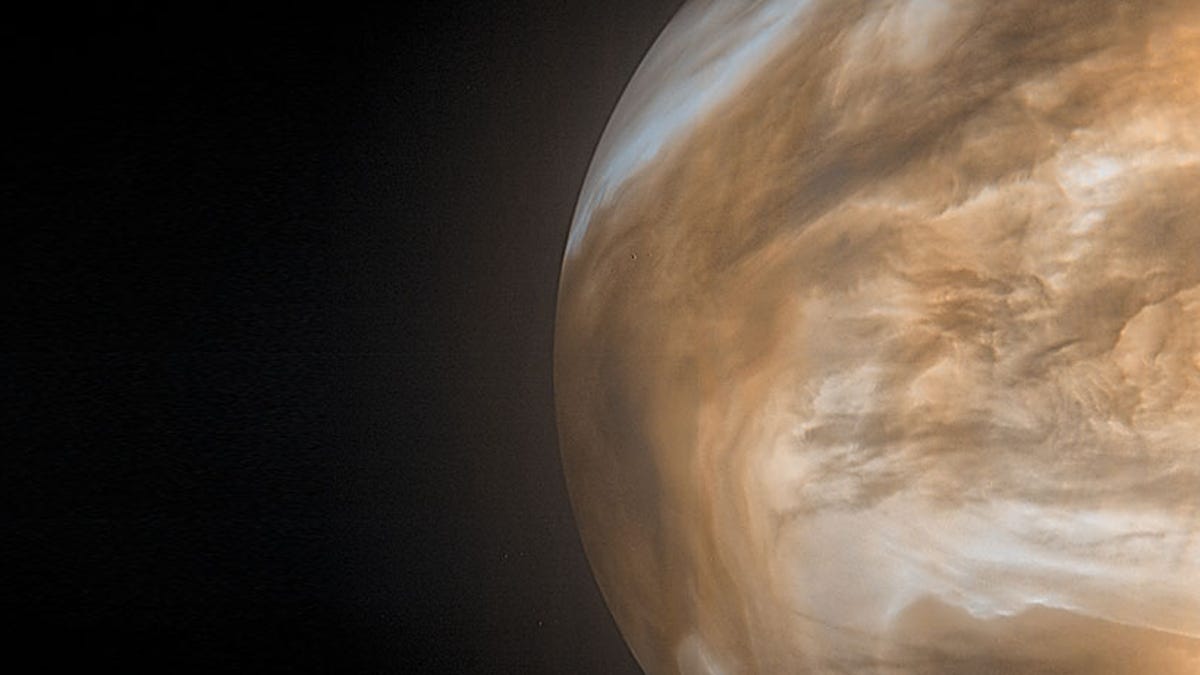

The presence of that phosphine on Venus may have been a mind-blowing revelation, which is because living organisms are one of the most recognizable sources of stinky gas. The team apparently responsible for the discovery, led by astronaut Jane Greaves of Cardiff University, found the evidence in celestial signals collected by two radio vessels: the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) and the Atacama Large Millimeter. / submillimeter Array (ALMA). Celestial lines at specific waves indicate the presence of certain chemicals, and in this case they meant the presence of phosphine in the cover of Venusian clouds.

The authors of the study Nature did not claim that there is life on Venus. Instead, they asked the scientific community to explain their rather strange view. In fact, it was a unique application, as it meant that Venus – one of the most unstable planets in the solar system – could actually live, with growth. -microscopic devices floating through the clouds.

Of course, this does not seem to be the case.

“Instead of phosphine in the clouds of Venus, the data are consistent with another hypothesis: They were looking for sulfur dioxide,” explained Victoria Meadows, co-author of the new study and professor of astronomy at University of Washington in a recitation. “Sulfur dioxide is the third most common chemical in the Venus atmosphere, and is not seen as a sign of life.”

G / O Media may receive a commission

Meadows, along with researchers from NASA, the Georgia Institute of Technology, and the University of California, Riverside, came to this conclusion by shaping a situation within Venusian sentiment, which they did to redefine the radio data collected by the original team.

“This is a radiation motion model, and it incorporates data from the value of several decades of observation of Venus from a number of sources, including observatories here on Earth and spacecraft missions. as Venus Express, ”Andrew Lincowski, a researcher with the UW Department of Astronomy and lead author of the paper, explained in the statement.

Equipped with the model, the researchers simulated celestial lines made of phosphine and sulfur at several atmospheric altitudes on Venus, as well as how ALMA and JCMT got these names. Results showed that the shape of the signal, found at 266.94 gigahertz, tended to come from the Venusian mesosphere – an extreme height where sulfur dioxide can be present but phosphine cannot be present due to harsh situation there, according to a study. In fact, this environment is so extreme that phosphine does not last more than a few seconds.

As the authors argue, the original researchers did not produce as much sulfur dioxide in the Venusian atmosphere and instead gave the signal 266.94 gigahertz to phosphine (both phosphine and sulfa are two -oxide including radio waves around this frequency). This, according to the researchers, was due to an “undesirable side effect” known as celestial line attenuation, NASA study co-author and JPL scientist Alex Akins explained in the report.

“They found a low trace of sulfur dioxide because of [an] an artistically weak signal from ALMA, ”Lincowski said. “But our modeling suggests that the diluted line ALMA data would still be consistent with normal or even large amounts of Venus sulfur dioxide, which could fully explain the JCMT signal. seen. ”

This new product could be devastating for the paper Nature, and it will be interesting to hear how the authors respond to this latest criticism. That said, some scientists believe the writing is already on the wall, or more accurately, the trash bin.

“Already shortly after the publication of the original work, we and others have cast strong doubts about their study,” Ignas Snellen, a professor at Leiden University, wrote in an email. “Now, I personally think this is the last nail in the chest of the phosphine hypothesis. Of course, one cannot prove that Venus is completely free of phosphine, but at least there is no evidence left now to suggest otherwise. I’m sure others will keep watching though. ”

Back in December, Snellen and his colleagues challenged the Nature study, arguing that the approach used by Greaves’ team meant that a high signal-to-sound ratio was “sputum” and that there was no “evidence”. statistically ”for phosphine on Venus.

Venus does not appear to have phosphine, and so without any notions of microbial life, far more interesting than otherwise, but that is how it sometimes goes. Science makes no claims or promises about the intriguing nature of everything, and we, as defenders of the scientific method, must come to accept the universe that we do not have as we find it. .