The second last jump was added on December 31, 2016, just before midnight UTC.

The International Service of Global Circulation and Reference Systems announced in July 2020 that there would be no second jump to the official world time hold in December 2020. The second last jump was December 31, 2016 .Because jump seconds are always set on the last day of June or December, the next possible date for a second jump is 30 June 2021.

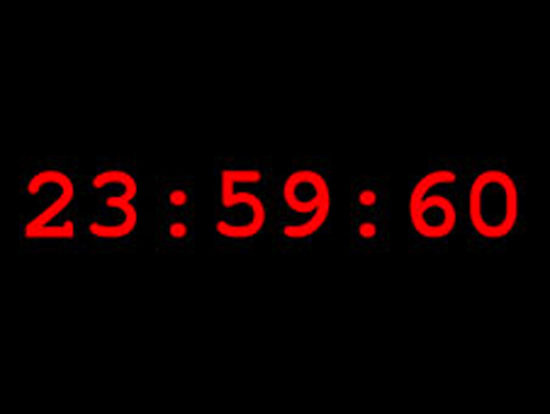

Jump seconds have been added 27 times since 1972. Jump seconds were added on June 30, 2015, and June 30, 2012. They are always added to the world clocks at 23 hours, 59 minutes and 59 Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) seconds, on 30 June or 31 December.

The latter is added to our official timekeeping especially to keep our ever-electronic world in sync.

Image through NASA.

Why do we need to jump in second place? Isn’t the length of our day determined by the Earth’s rotation? Like the ancients who demanded that all movements in the heavens must be perfect, uniform and unchanged, many of us today accept that the Earth’s rotation – spun on its axis – completely stable. We have learned, rightly, that the sun, moon, stars and planets are orbiting our skies as the Earth turns. So it is easy to understand why we assume that the rotation of the Earth is precise and unexpected. But the Earth’s rotation does not remain completely stable.

Instead, in contrast to modern time-consuming methods such as atomic clocks, the Earth is very bad. All in all, as many know, the spinning of the Earth slows down. Our length of day is increasing. A Wikipedia entry on this topic explains well:

The Earth’s rotation slows slightly with time; therefore, a shorter day was in the past. This is due to the tidal influence of the moon on the Earth’s orbit. Atomic clocks show that today is longer by about 1.7 milliseconds than it was a hundred years ago, slowly increasing the rate at which UTC has changed by leap seconds. Analysis of historical astronomical records shows slow movement; daytime has increased by about 2.3 milliseconds per century since the 8th century BCE.

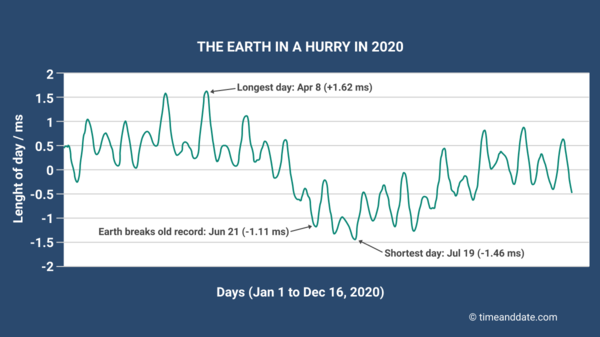

Earth’s rotation is slowing down, but it can also accelerate. The drag is a complete movement. The greater the speed of daily wonder. TimeandDate has a very interesting article on small speed in Earth orbit in 2020.

The fact is, the Earth’s rotation is subject to well-unpredictable influences. Short-term and other invisible changes can be caused by a number of events, from small changes in the circulation of mass in the Earth’s molten outer core, to the movement of large volumes of ice near the poles, and even changes in density and square momentum in the Earth’s atmosphere.

For example, you may remember the devastating Fukushima earthquake that hit northeastern Japan in 2011. It was a 9.0 magnitude earthquake, the largest earthquake recorded ever in Japan, and was the 4th largest earthquake in the world since 1900. It triggered a powerful tsunami. that killed about 16,000 people and led to a nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. It also caused parts of the Earth’s crust to dislodge the Earth’s orbit, shortening the day by 1.6 million seconds.

Daytime change throughout 2020. Daytime is shown as the difference in millions of nautical miles between the Earth’s rotation and 86,400 seconds. Image via “Earth Is in a Hurry in 2020” article at TimeandDate.com.

The reason for the slow rotation of the Earth is well understood. If you’ve ever been to the beach, you’ll know the main reason our planet slows down. That reason is tidal. As our planet orbits, it plows past the large aquatic ditches (built mostly by the gravity interaction of the Earth and the moon), which slows it down more slowly as a brake on. rotating wheel. This effect is small, in fact very small. According to calculations based on the time of eclipses, Earth’s orbit has slowed by about .0015 to .002 seconds per day per century.

The Earth is slowing down, very slowly. It will take about 100 years for the Earth’s orbit to add just 0.002 seconds to the time it takes the Earth to spin once on its axis. What happens, however, is that the 0.002-second daily difference between the original definition of a day (86,400 seconds) builds.

After one day it is 0.002 seconds. After two days it is 0.004 seconds. After three days it is 0.006 seconds and so on. After about a year and a half, the difference goes to about 1 second. It is this difference that has inspired an additional leap.

All of this is monitored, today, very high by atomic clocks (which are accurate to around a billion seconds per day).

And of course the slowdown is not stable either. According to the U.S. Naval Observatory, between 1973 and 2008, the difference in Earth spinning has ranged from 4 milliseconds to 1 millisecond. Over time, that may require a negative jump in the second place, signaling an increase in the Earth’s orbital speed.

However, since the idea of leap seconds was introduced in 1973, this has never been done.

And, by the way, if this detail seems to have kept you esoteric or unimportant, understand that it is not for the telecommunications industry.

Modern telecommunications are time-dependent, and by leaps and bounds many systems are turned off for a second every year or two. That’s why there are sometimes conversations about eliminating a jump tick. Image via aie195.com.

Not everyone thinks jumping in the second place is a good idea. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a United Nations body that governs some global time-related issues, has been considering leapfrogging seconds for some time. They considered scrapping the practice, but in November, 2015 – with representatives from more than 150 countries meeting in Geneva – the ITU announced its decision. No to dump the jump in second place, at least not right now. The ITU said:

The decision co calls for further studies on current and future reference timescales, including their impact and applications. A report by the World Radiocommunication Conference in 2023 will be considered.

So they are still thinking about it.

Consider the position of the ITU. Telecommunications are time-dependent, and by leaps and bounds many systems are turned off for a second every two years. Getting all such systems in the global cycling industry on and off in sync can be a major headache. Also consider that the global positioning system (GPS) does not use the second jump system, which causes further confusion. Many in the industry feel that adding from time to time to a second step to keep steps a difficult and wasteful step.

While it would be a facility for telecommunications and other businesses to dismiss the idea of a second-rate jump, in the long run (very long), it would force clocks to get out of the sun, and finally 12pm (noon) would cause midnight to happen, for example. At the current rate of change in the Earth’s rotation rate, it would take about 5,000 years to build just an hour-long difference between the Earth’s flat rate and the atomic clock.

How, you may be asking, do we even measure such small changes in the Earth’s orbit? Historically, astronomers (such as those at the Royal Greenwich Observatory near London) have used a telescope to see a star through their eyes, crossing an imaginary line known as the morning. Then they take a while as long as it takes the Earth to bring that star back around to cross the morning again. This is highly inaccurate for everyday purposes, but for scientific use it is limited in accuracy due to the waves used and the murkiness of the atmosphere.

A much more accurate method is to use two or more radio telescopes separated by thousands of miles, in a method called Very Long Baseline Interferometry. By carefully combining the data from each of the telescopes, astronauts effectively have telescopes of thousands of sizes, which provide much larger resolution (finding details) and position measurement. This allows them to determine the orbit of the planet in an accuracy of less than a thousandth of a second. They do not track stars, however, but distant objects called quasars. The NASA video below will tell you more…

Baseline: There will be no second jump to official timekeeping on 31 December 2020. World timekeepers will consider a proposal to dump the jump in second place in 2023. Watch out, keepers time!

Read more from PhysicsWorld: A brief history of timekeeping