Scientists have unveiled a study of a meteorite chip that was collected after a 2008 near-speed crash with Earth. They show that the parent asteroid was quite large, and the findings suggest that certain types of asteroids, which hold water, can be larger and have different mineral shapes than expected. before.

The findings of the survey published this week in the journal Nature Astronomy and look at the sliver chemical composition of these meteorite fragments.

The story of the particles begins in October 2008, when scientists became aware of an asteroid on its orbit. They knew that most of the rock would burn up as they entered the Earth’s atmosphere, and that what was left, if any, would fall into the windy sands of the Nubian Desert. . It gave an international team of researchers, including NASA scientists, a unique opportunity to expect the rocks to reach and then comb the sand for any surviving fragments.

Although the asteroid was relatively small – only about nine tons – its detritus was not small; less than 8.8 pounds (4 kilograms) meteorite was collected from the desert. They named it Almahata Sitta, after a nearby railway station. This was the first time an asteroid was seen and then the remnants of meteorite were collected.

G / O Media may receive a commission

Since its recovery, various fragments from Almahata Sitta have been studied, revealing information about the origin and chemical forms of different parts of the asteroid. The meteorite sample surveyed by the team–called AhS 202 – it was so small that you could put 10 copies of it on a nail head, but it came from a gargantuan space rock, a starting point that is ahead of the coming of the chip along the rocky mound of Almahata Sitta. The team used infrared light and x-ray to examine the sample. They found that the crumb was a carbonaceous chondrite, a type of meteorite formed in the early days of the solar system, and which may have caused water to enter the Earth. .. everything. It was not previously thought that carbonaceous chondrites could come from parent groups (asteroids of origin) larger than about 62 miles (100 kilometers) in diameter.

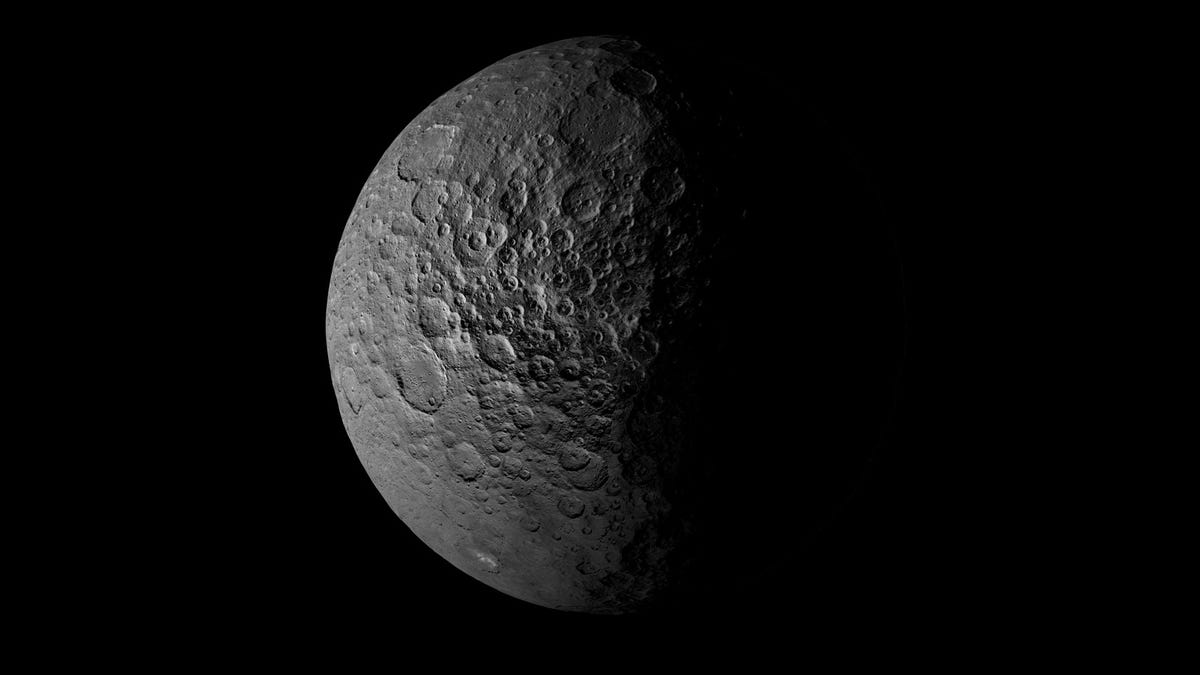

But the researchers found tremolite in their ity-bitsy chip, a mineral that needs a lot of pressure to form. Tremolite in the sample indicates that the asteroid diameter of origin is in the range of 398 to over 1,119 miles (640 to over 1,800 kilometers), placed in Ceres wheelhouse, mainly—a deep planet, of course– in the asteroid belt.

“This is a piece of evidence for a very large, previously unknown group of parents,” said Vicky Hamilton, a staff scientist at the South West Research Institute and a recent lead author of the paper. note that this is the first known presence of tremolite in carbonaceous chondrite. “The fact that we have no other evidence for it in our meteorite collections helps to confirm what we already suspected is that the dragons we find on Earth are samples claon. ”

As asteroids explode through space, they must communicate with other bodies. These accumulations of metals and minerals converge and separate as their path continues. When a meteorite is found on Earth, it is a collection of stories from space, and the only way to read it is to do a handful of analyzes.

“You can have one group of scientists look at one piece of meteorite and another group look at another piece of that same meteorite, and you see two different parts of the history of the solar system,” Hamilton said.

That’s how Hamilton’s slower could talk to some originator at high speed, and another piece of Almahata Sitta could be advertising at the on proto-planet life. The electroscopy work done by the team recently is a kind of reverse engineering, to go from something resembling a normal space rock to its unique story, in this case referring to a grandparent asteroid. It’s like finding a lump on your kitchen counter – it could be from anywhere – but looking at it chemically could tell you the temperature and pressure it caused, and whether that crab came from this morning’s silence or last week’s birthday cake.

Although much rarer than other types of asteroids, new information about carbonaceous chondrites could fall from the sky at any moment. It’s just a matter of whether meteoriticists are observant – or lucky – enough to see them.