Sales inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), grew at 5% in February 2021 year on year. February figures also include a reversal of falling inflation from November 2020 to January this year. What does this mean for the larger macro economy? Here are four charts that show the latest inflation figures.

1. Non-food prices were rising for a while, only food prices were now moving beyond their movement

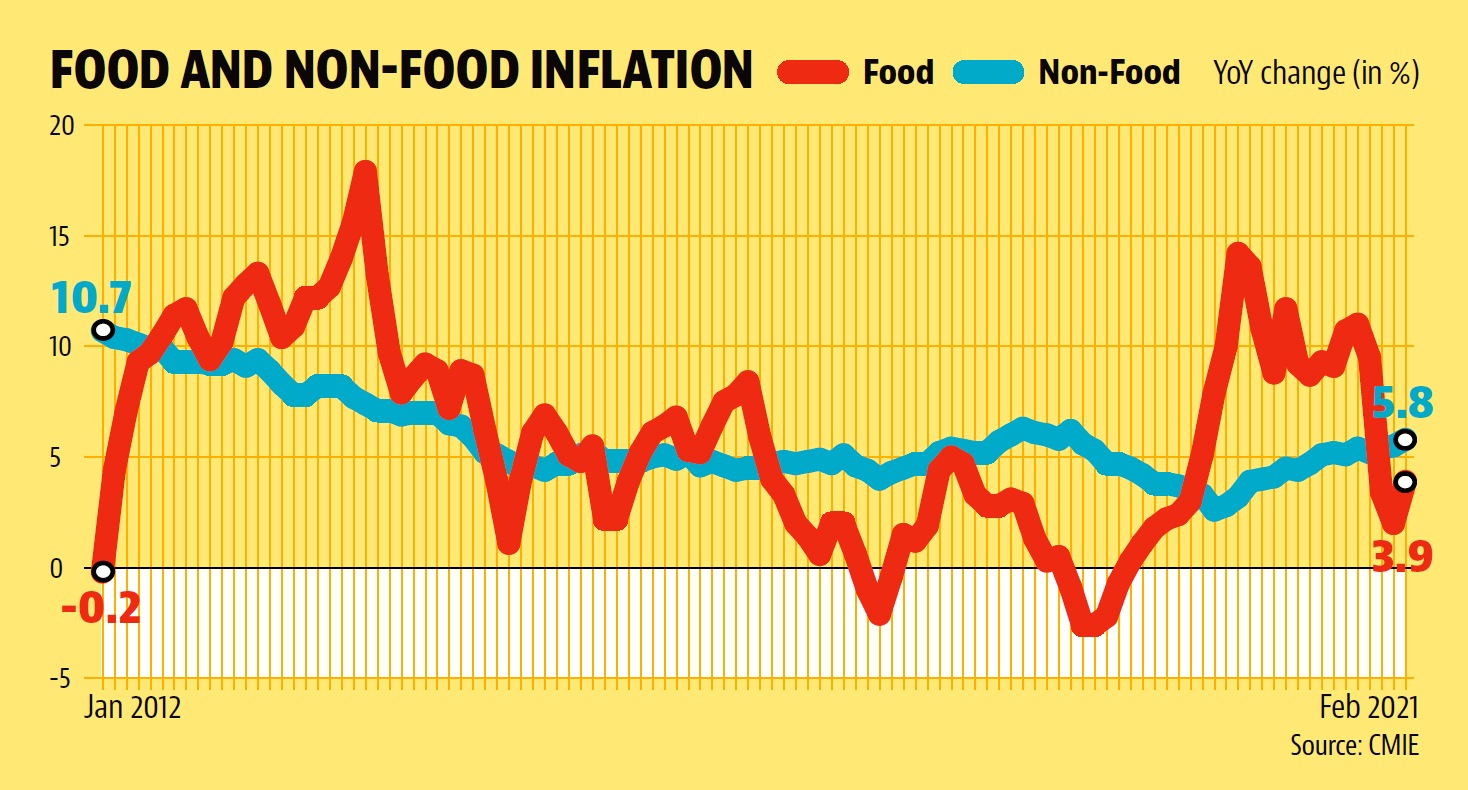

39% of India’s CPI basket is made up of food products. This means that headline inflation is highly sensitive to what is happening to food prices. The recent fall in mainline inflation; it fell from 7.61% in October 2020 to 4.06% in January 2021, before rising to 5.03% in February, largely a reflection of moderation in food inflation, which fell sharply from 11% in October 2020 to just 1.96% in January 2021.

Also read: Factory production contracts in January hit a 3-month high

Prices of non-food products have never changed at this time. The non-food basket of CPI grew at 5.39% in October 2020, modeled slightly to 5.23% in November 2020 and has risen steadily in the last three months to Reach 5.78% in February 2021. The value of non-food inflation in February 2021 is at its highest level since October 2018.

2. What caused an increase in food inflation?

The most important question is what did not.

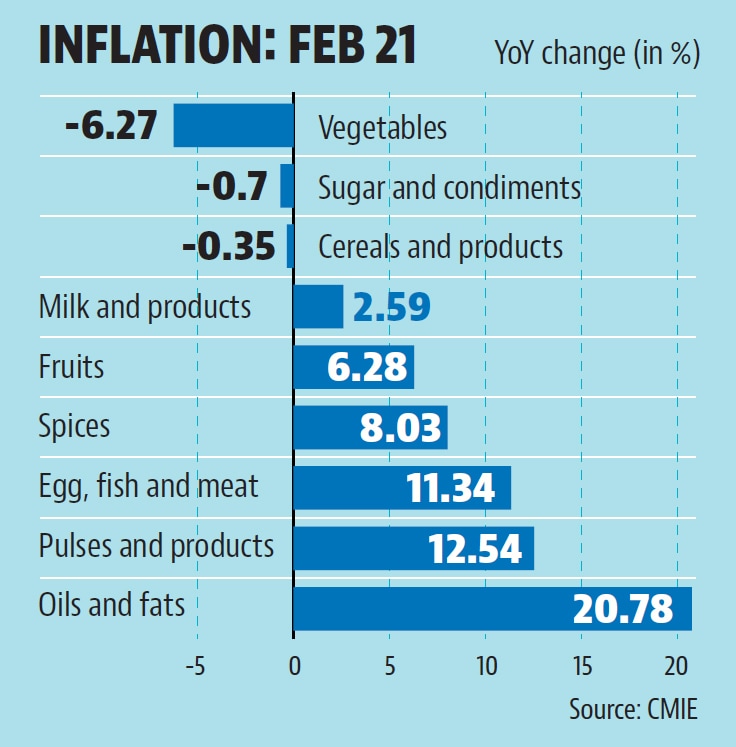

Prices of grain and produce, vegetables and sugar and condiments – these three subgroups make up nearly half of the CPI food basket – were lower in February 2021 than they were in February 2020. This is the first case since January 2012, the earliest period for which data are available under the current CPI series, that inflation for grain and yields has entered negative territory. Vegetable prices continued to fall, albeit at a slower rate, largely due to tensions in onion and tomato prices. The commodity group that has been sharp in its February prices is the edible oil (fat) sector. At 20.78%, inflation in this sector is at an all-time high since January 2012. This group has been experiencing uninterrupted double-digit inflation since April 2020. Prices of beef, fish and fish products have risen. eggs also in double numbers in February, again continuing. of long-term movement.

3. What causes non-food inflation?

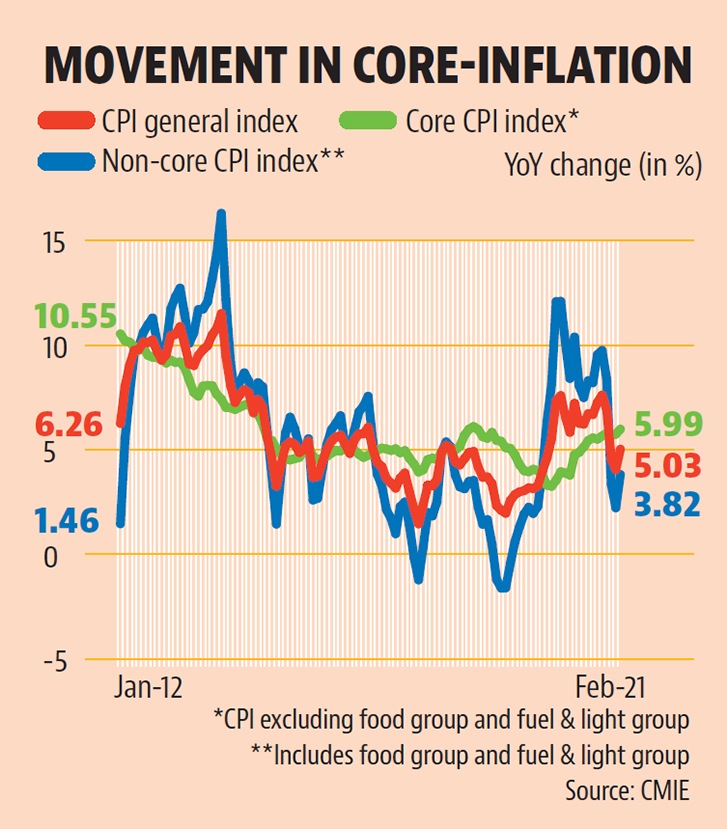

There is more to fuel prices. Core inflation, which measures the path of the non-food basket of CPI, grew at 5.99% in February 2021, the highest level since July 2018.

A look at the broad subdivisions of inflation shows that it is clothing and footwear and the mixed sector under the CPI; the latter has the highest weight gain of 28.32% after meals, which shows an increase in February compared to the previous month. Another divergence shows that prices for almost everything in the mixed sector, with the exception of care and personal effects, gained momentum in February. Transport and communications, which make up nearly 30% of this sector, have re-entered the area of double-digit inflation. This essentially means that carriers are giving up pain in rising fuel prices to consumers. The movement in the prices of these items is in line with what experts such as Pranjul Bhandari, India’s chief economist of HSBC Securities and Capital Markets, have said about the potential recovery in services inflation once the economy opens .

4. These are the broad trends of inflation. But what does it mean for the economy?

It is bad news for rural demand.

For three months in a row now, the prices of non-food items have been rising at a faster pace than food items. This means worsening trading conditions – the ratio of disposable prices and payments – to farmers. As discussed above, the main food inflation figures do not capture the true picture of farmers ’heads for farmers’ welfare.

Also read: Expensive food, higher fuel prices drive 3-month high sales inflation of 5.03%

Grains, vegetables and sugar (canister); the three food groups that suffered disinfection in February make up more than half of the value of the product in Indian agriculture. However, there is less pressure in the overall product basket and large import content of food items that has seen a rise in prices. Farmers who grow grain, vegetables and sugar simply have to buy more money to buy things from the market, while getting a lower price for what they take to sell to the market. market. This is related to stressing their purchasing power and therefore demand.

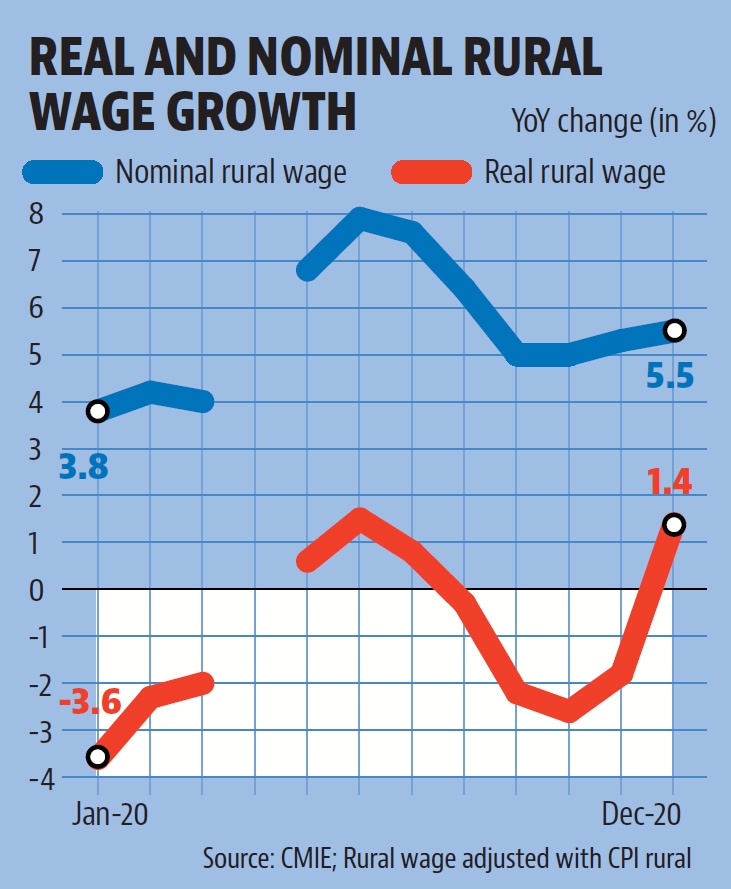

Farm incomes are not the only variables affected by the current rise in inflation. We have rural wage data up to December 2020. Average rural wages came out of the shortening range after four consecutive months in December 2020. This was largely due to a change in inflation. A simple comparison of actual and projected wage growth in November and December 2020 yields this. While real rural wages grew 3.2 percentage points in those two months, nominal wage growth grew by just a quarter of a percentage point. If inflation were to reverse its fall, as it is in February, it could create strong headlines for rural wages, and therefore demand as well.

Of course, rural demand is not the only sector that suffers from rising inflation. There is a strong consensus in the table that India’s post-pandemic economic recovery has thrown blades in favor of capital and away from labor, or something called a profit-based recovery. Private estimates such as the one by the Center for Indian Economic Studies suggest that labor force participation rates, which measure the proportion of working-age people working or looking for work, have not returned to pre-employment levels. -pandemic. India is also currently facing a second wave of Covid-19. This has the potential to prevent supply chains and re-stimulate inflation. India’s economy is also facing international problems with inflation; Commodity prices, particularly crude oil, have been rising and are expected to either hold a course or not come down anytime soon, as advanced rural economies gather momentum , thanks to stimulant packs and vaccines. All of this has the potential to put pressure on real income and therefore total demand.