A crater that covers nearly a quarter of the moon’s surface has unveiled new information on how a buddy created Earth’s natural satellite – and the findings have a major impact, researchers say.

A new study of the material extracted from the effects of the South Pole-Aitken basin has allowed scientists to update the timeline of the development of the lunar and bark costume, using radioactive thorium to order the find events.

“These results,” wrote a team of researchers led by planetary astronomer Daniel Moriarty from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, “have a significant impact on the formation and evolution of the moon.”

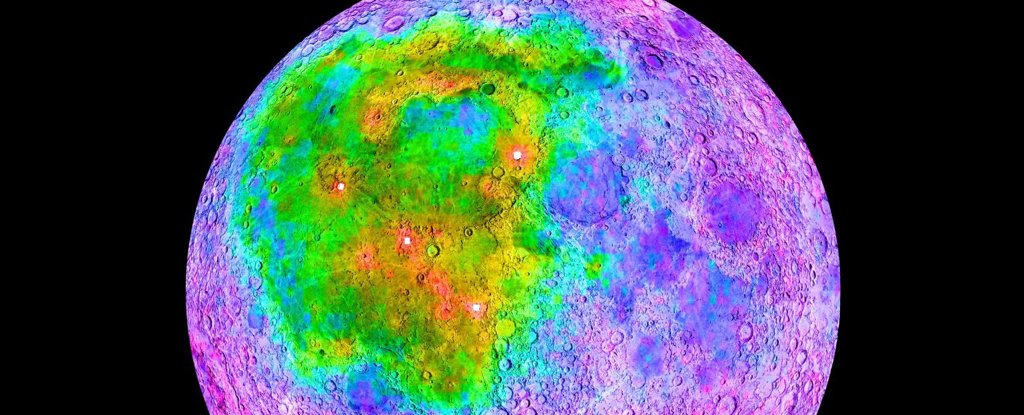

On a Moon that is completely covered with impact splits, the South Pole basin stands out. At 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles) across and up to 8.2 kilometers (5.1 miles) deep, it is one of the most influential faults in the Solar System.

It was achieved with great impact around 4.3 billion years ago, when the Solar System (currently 4.5 billion years old) was still a child. At this time, the Moon was still very warm and accessible, and the effect of “spraying” on many materials would be from being below the surface.

Because the hollow is on the other side of the moon, it was not as easy to study as the other side of the Moon. Researchers have now simulated the shower pattern from the impact of the South Pole, and found out where the ejecta should have fallen in response to thorium deposits on the lunar surface. .

One of the unique things about the Moon is that the near and the other side are very different from each other. The near side – which is always opposite the Earth – is covered with dark splotches. These are the lunar maria, vast expanses of dark basalt from ancient volcanic activity within the moon.

In contrast, the other side is much paler, with less basalt packing, and a lot more filters. The bark on the opposite side is thicker, too, and has a different consistency from the adjacent side.

Most of the thorium we find appears on the near side, so its presence is usually described as a connection to this difference between the two sides. But a link to an ejecta from the South Pole-Aitken influence tells a different story.

The lunar thorium was deposited at a time called the Lunar Magma Ocean. At this time, about 4.5 to 4.4 billion years ago, the Moon is thought to have been covered by molten rock that was gradually cooling and solidifying.

During this process, minerals went deeper into the bottom of the molten layer to form the mantle, and lighter elements stretched to the top to form the crust. Since thorium is not easily absorbed into mineral structures, it would have remained in the molten layer that existed between these two layers, simply descending towards the heart during or after the crystallization of the bark and the mantle.

According to the new analysis, when the South Pole-Aitken impact hit, it dug up a handful of thorium from this layer, splashing it over the lunar surface on the near side.

This means that the effect would have existed before the thorium level was lowered. He also suggests that the thorium level at that time must have been distributed throughout the globe, rather than concentrated on the moon near the side.

The South Pole-Aitken effect also melted rock from a deeper depth than the ejecta. Consistently, this is very different from the material sprayed over the surface, with very little thorium. At the same time, this indicates that there were two different layers in the mantle at the time of the exposure that were exposed in different ways.

Since then the impact shower material has been covered by more than 4 billion years of eruption and weather and volcanic activity, but the team found several pristine thorium deposits in an impact crack recently. These will be important sites for future lunar missions.

“The creation of the South Pole-Aitken Pool is one of the oldest and most important events in the lunar history. Not only did it influence the thermal and chemical evolution of the lunar eclipse, but it preserved insect materials. heterogeneous on the lunar surface in the form of an ejecta and the effect of melting, ”the researchers wrote in their paper.

“As we enter a new era of international and commercial lunar study, these bonding materials at the lunar surface must be considered among the highest priority targets for the advancement of planetary science.”

The research was published in JGR Plans.