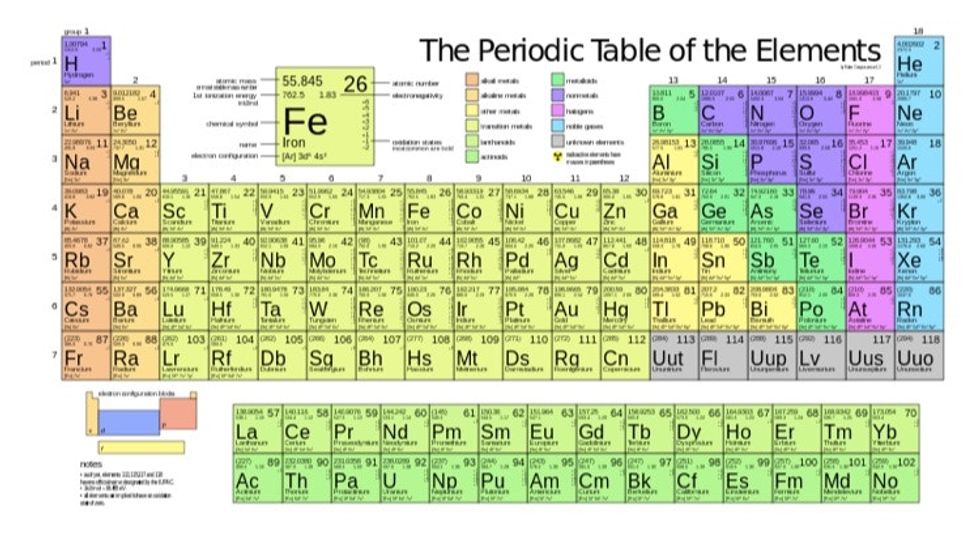

The table of elements is periodically viewed by millions of people every day.

It is a landmark image and the chemistry map that has been tested.

Also available in placemat, coffee mug, and shower curtain. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s basically in every science room in the world along with that skeleton that your teacher named Boney, Skinny, Jerry, or whatever.

“Class, we have a new student today. His name is Jimmy McRib.” Photo by Douglas Grundy / Three Lions / Getty Images.

You may not be aware that the quarterly schedule is endless.

Well, sort of. Not true end to the number of chemical elements that can be present. Elements are detected and identified by the amount of proteins in the nuclei. For example, hydrogen: one proton in its nucleus. Lithium: three proteins in its nucleus. Iridium: 77 protons in its nucleus, and so on.

To date, we have been able to view and name over 100 elements and sort them by that atomic number into the quarterly table – with only a handful of blank spots in the seventh row.

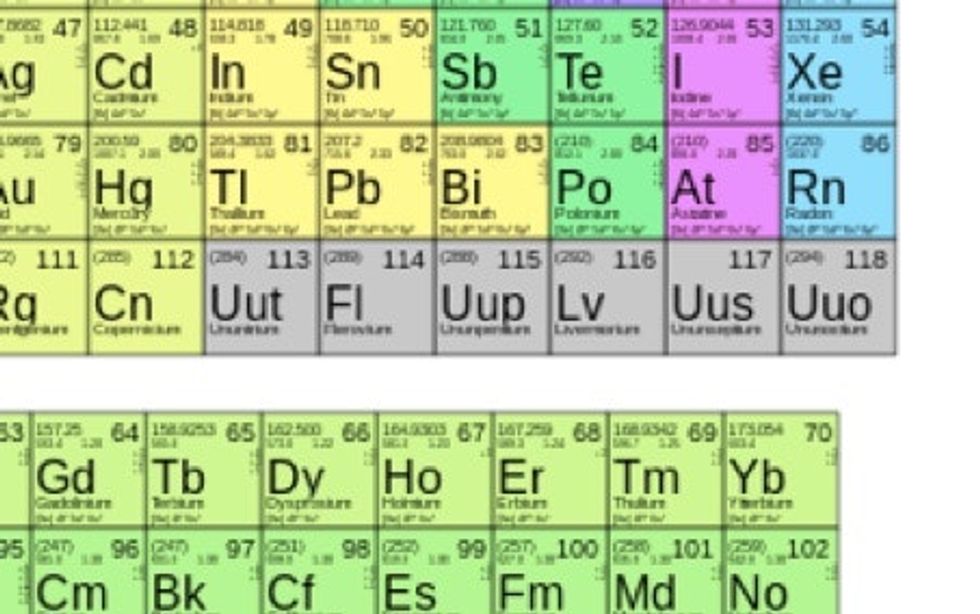

113, 115, 117, and 118 (in gray) have been left unknown so far. 114 and 116 were added in 2011.

On December 30, 2015, scientists from around the world could officially, finally, fill in these blank spots.

Elements 113, 115, 117, and 118 have been officially discovered and specified by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a U.S.-based organization that monitors global chemical names, terminology, and measurement.

The seventh “superheavy” series elements are the first to be added to the quarterly list from 114 and 116 back in 2011.

Until now, they have remained theoretical and have been given place names as “ununseptium,” 117 meaning “one-seven-seven” in Latin.

The new elements can be found in material accelerators similar to the famous Hadron Collider in Switzerland. Photo by Fabrice Coffrini / AFP / Getty Images.

You can’t do much with these horrible elements, as they don’t occur in nature and are very unstable, decomposing faster than you can imagine.

However, a popular theory among scientists is that the more we learn about supernatural elements, the closer we get to an “island of stability” where large atoms do not decompose immediately. and may be useful.

In the coming months, the four new elements will get official names and make all chemistry textbooks out of time.

Elements 115, 117, and 118 have been credited and will be named by teams of Russian and American scientists.

Element 113, however, is a subconscious story itself.

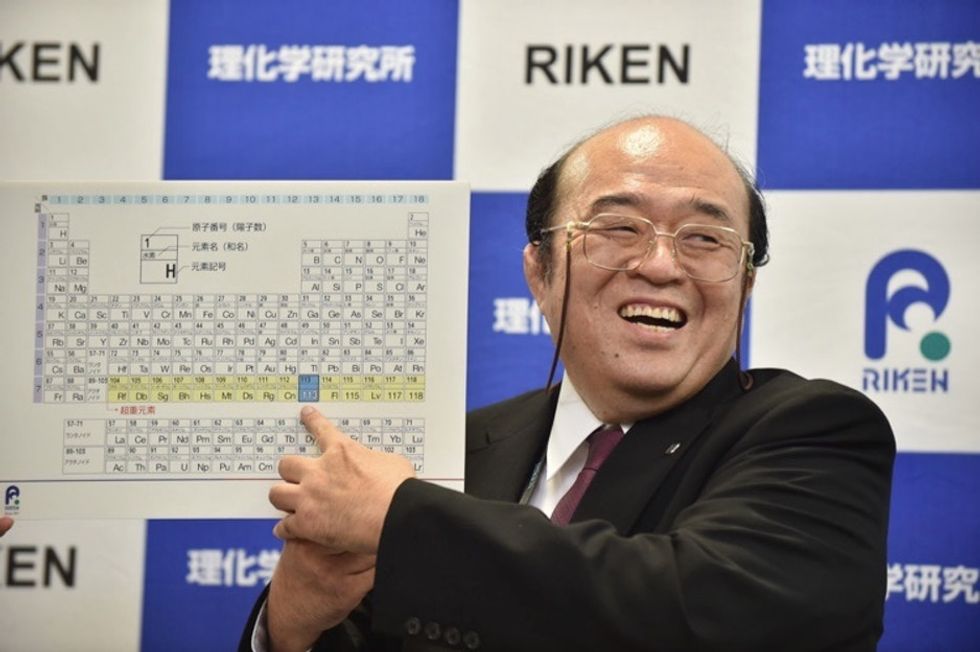

In 2003, Japanese scientists at RIKEN began “bombarding a thin layer of bismuth with zinc ions traveling at about 10% the speed of light,” you know, as you do.

The result of that experiment was one small, light view of an element with an atomic number of 113. They stuck to it, and eventually created 113 several times.

Although it lasted less than a thousandth of a second, it was enough for the IUPAC to name the first rights to an element given to Japan.

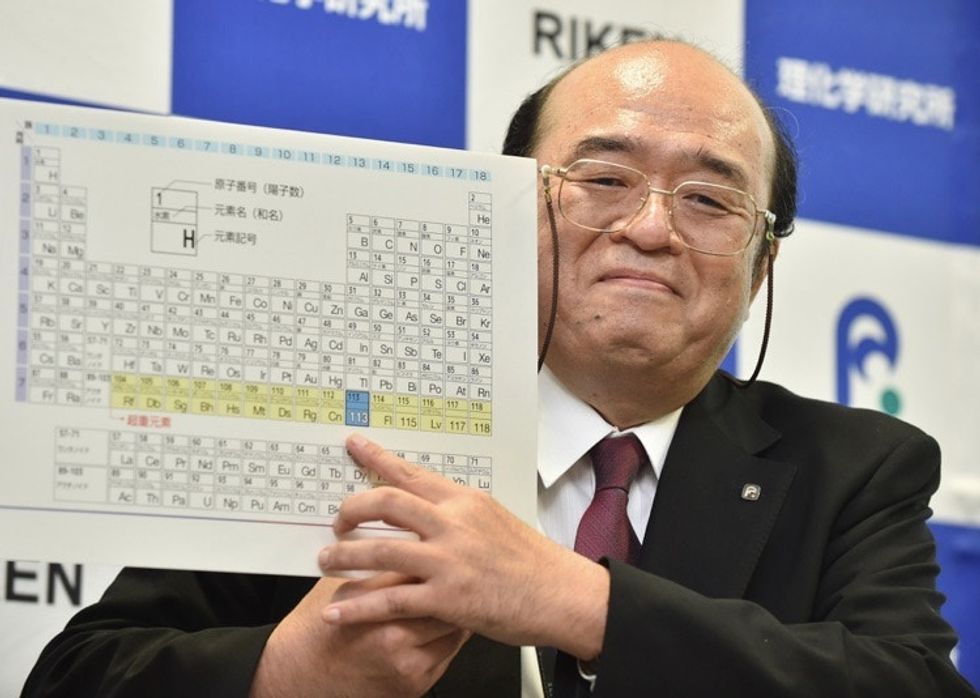

Kosuke Morita, proud father of element 113. Photo by Kazuhiro Nogi / AFP / Getty Images.

According to Kosuke Morita, leader of the RIKEN Japan team, the honor of naming an element “worth more than an Olympic gold medal” is for scientists.

Naming an element is not like naming a bridge. When you name an element, you put your stamp on the basic and permanent building block of the universe. You have established a place in history.

I just hope Morita and her team create a better name for 113 than your science teacher did for that skeleton.