A.t 92, Elliott Erwitt is one of the oldest men in photography. Over its 70-year career it has amassed an archive of around 600,000 images, the most famous of which has a quiet, witty charm that one of his friends, Henri Cartier-Bresson, described as “a laugh from the dead. his own depth ”.

Autonomous and old-fashioned in his ideas, Erwitt has been far removed from the contemporary picture movement, insisting that it is a craft rather than an art form. He once said that he was “a professional photographer by trade and an amateur photographer by profession”, which largely reflects the writing skill that informs his most famous images – the the introduction of a visual portrait of Jackie Kennedy grieving at her husband ‘s funeral and an angry Richard Nixon taking Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev by the chest in their famous heated debate in Moscow in 1959.

In his time, in addition to creating memorable portraits of celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe, Che Guevara and Simone de Beauvoir, Erwitt also chose themes that were often overlooked by more interesting reporters. Children show a great deal in his work; even bigger dogs – Woof and Mac na Bitch only two of his photographs are on a canine theme. Perhaps unsurprisingly, some critics consider this approach despicable, although American conservative John Szarkowski disagreed, citing Erwitt as “one of the few photographers who are also celebrated for their remarkable work ”.

Now, in old age, Erwitt has turned his attention to his vast archive of previously unseen work. While selecting images for his 2016 retrospective show, Home Around the World, at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, he found himself re-evaluating many previously photographed or viewed images. rejected outright. “It’s time for pictures that say hello,” he said of the thinking behind the process, “and there’s time to listen. ”

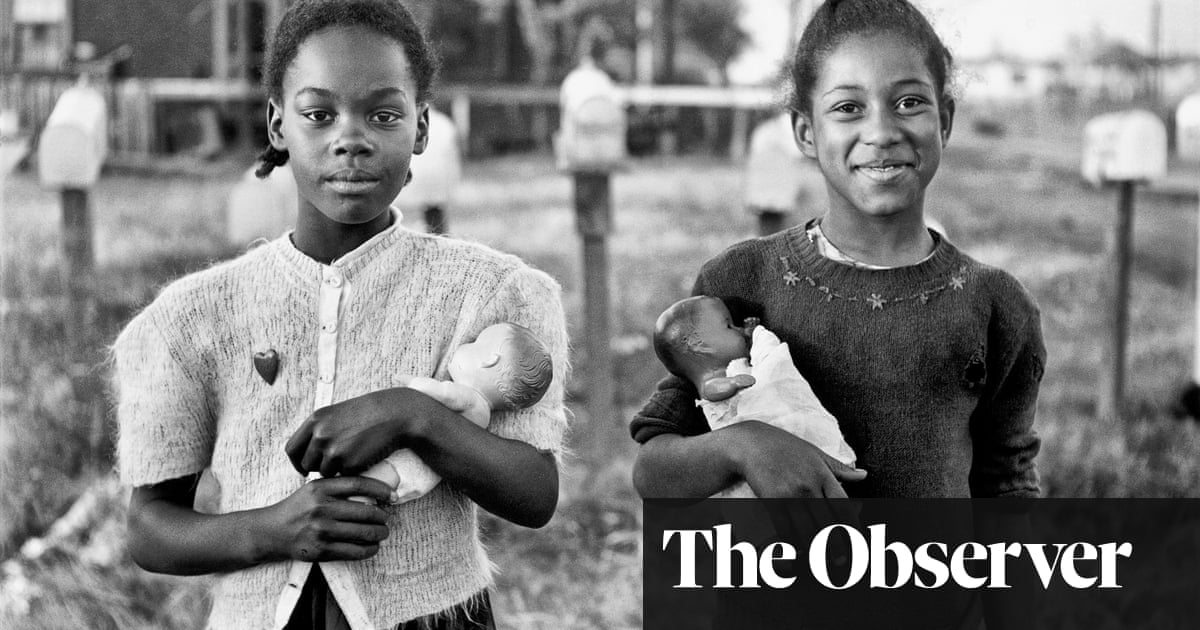

New book, Found, Not lost, collects these recovered images in a random manner that largely adheres to Erwitt’s resolute oeuvre. They were selected, edited, and ordered by Erwitt himself, and, as he responds to such a thoughtful effort, they often show a feeling of calm melancholy. It has included several studies of people caught in a moment of reverie, as well as scenes of passing figures, often shot from behind. At times, as in his photograph of two young black girls standing on a street in New Orleans in 1947, one attracting a black doll, and the other white, there is praise for a world outside the frame that is not charming or foolish. Elsewhere the fetus is closer, as in the soft portrait of his first wife, Lucienne van Kam, asleep on a bed in their New York apartment in 1954, one of several portraits of women in repose.

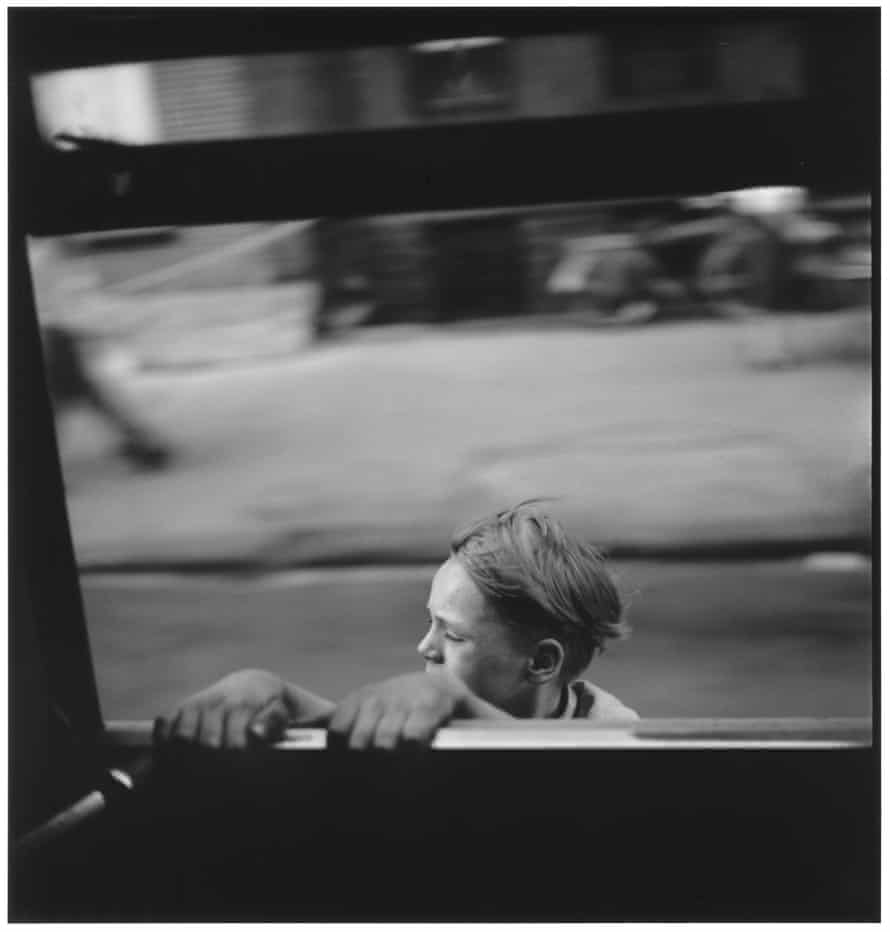

Erwitt’s street photography has a more refined approach than we expected from it, perhaps because many of them were taken at break times between editorial specifications. As a young photographer, he moved the streets of New York in the 1950s, aware of his energy and character. He caught tired passengers splashing over the seats of rattling subway trains, a young boy clinging tightly to the window frame of a moving bus, and a torso approaching a band in a parade, the buildings blur background above a large arc. druma. A bullet of a young boy about to kick a football on a piece of rubbish in Pittsburgh casts a blurred silhouette of his body against an obscene brick wall.

This stream of street photos and photos includes moments of unrest ranging from something – a young black man with a photo ID taken in an army recruiting center – to the incredibly dramatic man, such as a smiling man, borbited by a placard that reads Burn All Reds. The last one was taken at a fair display on June 19, 1953, the day Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed, convicted of treason for Russia.

Most of the pictures inside Found, Not losthowever, they are quieter looking in tone. They are largely infused with just the space and the year alone adds to the air of mystery that many build – often arising from the feeling that greater drama occur slightly beyond the frame. Erwitt is, among other things, an inexhaustible watchdog of other onlookers.

For all that, Erwitt’s whimsical charm is still to be seen throughout, with scenes of smiling children, sunbathers, and dancing couples. Perhaps a harder edit had turned Found, Not lost into a remarkable re-evaluation of his work; instead, it stands as the silent shadow history of a photographer who does not fit neatly into any tradition. Maverick with an eye for the intimacy as well as the fog.

Found, Not Lost published by Gost (£ 60)