It has been shown to be an important cell in the immune systems of mice and humans with gut-healing properties in mice with a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

In a new study, researchers have used the cell to boost the immune system to help repair damage in the gut of mice, rather than attacking them. They hope to one day target similar intestinal cells in patients with Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis.

Both of these diseases are caused by the immune system invading the lining of the gut, and most conventional medications aim to limit the immune response.

While these medications help, this broad approach knocks the good defensive players in with the bad, and sometimes, the same player can be a bit of both.

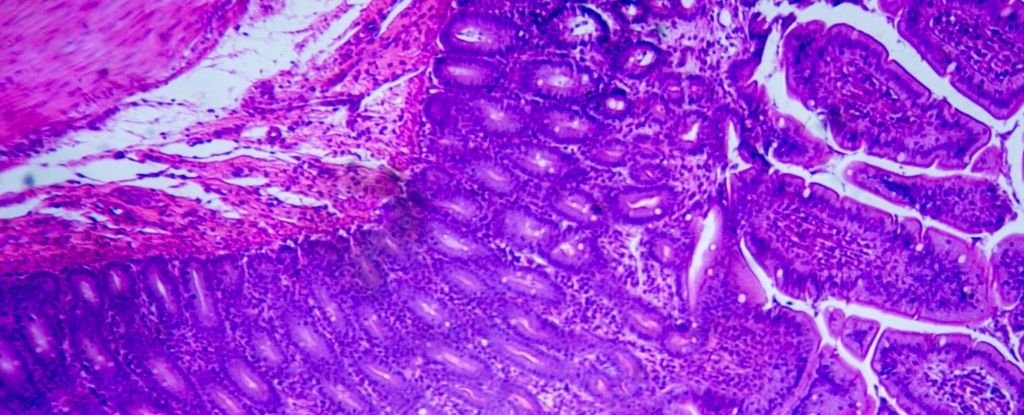

Macrophages, for example, are referred to as ‘gatekeepers’ of intestinal immunity. This type of white blood cell eats foreign bodies and plays an important role in inflammation and tissue repair.

His presence may therefore be necessary to overcome motivation. When researchers looked at macrophages in the intestines of people with IBD, there was one particular molecule that stood out.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a messenger molecule in the immune system. It is also linked to regenerative tension, producing macrophages that then communicate with stem cells in the lining of the sphincter.

Compared with a database of information about healthy individuals, researchers found that the colon of those with IBD showed fewer intestinal macrophages with receptors for prostaglandin (PGE).

It is these receptors that receive messages about gut injury, but the signal cannot get through to intestinal stem cells unless the macrophages can heed the warning and begin the healing process.

“If the patients had a serious infection, they would have fewer of those beneficial cells, and if they went into remission, volumes of macrophages went up,” KU Leuven immunologist Gianluca Matteoli explained in Flanders, Belgium.

“This suggests that they are part of the compensation process.”

If the authors are correct, the findings may represent a new pathway for novel drugs to treat IBD, and while there is still a long way to go before that happens, initial experiments on mice have showing promising results.

Similar to what was observed in humans, the authors found that animal models with ulcerative colitis did not possess as many prostaglandin-sensitive macrophages compared with healthy controls.

However, if additional prostaglandin was ingested into the spleen, the few PGE2-sensitive macrophages began to stimulate the regeneration of tension. When these receptors were completely demolished, the repair of cloth fell again.

Taken together, the findings support the view that macrophages are the main drivers in tension regeneration after inflammation in the esophagus. By binding to receptors on these intestinal white blood cells, PGE2 appears to inhibit inflammation and induce protective effects.

Unfortunately, scientists do not yet know the true source of intestinal PGE2, but because macrophages want to eat foreign matter it is easier to target them with synthetic drugs, such as prostaglandin.

When the authors introduced intestinal macrophages in the gut of the mouse to eat up juicy bubbles of stimulant ‘medicine’, it stimulated the secretion of a repair agent, which stimulated further cell proliferation and organic organisms.

This method of feeding macrophages is often used as an experimental device, but this is one of the first times it has been used to therapeutic effect.

“We want to identify other factors that will cycle the conversion of macrophages from inflammatory cells to non-inflammatory cells,” says Matteoli.

“Then … these could be used to target the macrophages and thus make drugs very precise.”

The study was published in Gut.