It has been a year since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic.

In the 12 months since, the UK, like the rest of the world, has experienced what public health experts have been feeling for decades: a dangerous new virus that would emerge to spread quickly. across the globe.

2020 began with the scientific and medical communities knowing almost nothing about the mysterious virus affecting the Chinese city of Wuhan.

It would end with COVID-19 vaccines going off the product line.

The tragedy is COVID-19

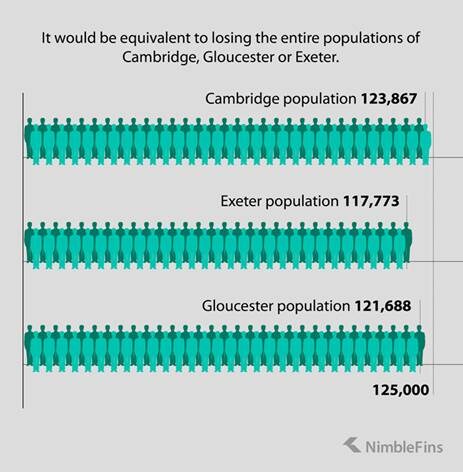

In between we saw the daily number of traumatic deaths rising from the first in Berkshire in early March last year to 125,343 today.

That was the equivalent of losing the population of a city the size of Cambridge, Exeter, or Gloucester.

Credit: NimbleFins

A year ago, Sir Patrick Vallance, the Government’s chief scientific adviser, said that 20,000 deaths in the UK from COVID-19, even if “horrible”, would be a “good result”.

In the last 12 months, we have seen health services and health workers under incredible pressure and pressure, we learned what it was like to live in a lock, wash hands while singing happy birthday, clapping for caregivers, discovering the meaning of furlough, finding a home for our children, buying masks, experiencing support bubbles , and we learned more about an eye test at Barnard Castle.

But we have also discovered how international scientific cooperation could create vaccines to protect against this disease in a short-lived, breath-taking order.

Alarming Virus

It was on 11 March 2020 that Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO’s director general, told reporters of the “alarming rates of spread and severity” of the new virus and the “alarming levels of activity”.

As a result, “we have therefore assessed that COVID-19 can be identified as a pandemic,” he said. “We have rung the loud and clear alarm bell.”

During the first 3 weeks of the New Year, the so-called SARS-CoV-2 virus and the COVID-19 infection it caused remained a distant threat to the UK.

Then, on 22 January, Public Health England raised the risk level for the novel coronavirus from ‘very low’ to ‘very low’.

It was an ominous warning. One week later, the first two patients in the UK, both Chinese nationals, tested positive for COVID-19. On February 6, a third person was found to have contracted the virus while at a conference in Singapore.

On February 28, the first Briton – a passenger on the Diamond Princess cruise ship – was confirmed dead by the Japanese authorities.

On March 3, the Government published an action plan to deal with a modern-day coronavirus that included the scenario of “a very long pandemic as of 1918”.

The next day, just a week before the WHO declared a global pandemic, the total number of confirmed cases in the UK reached 85.

On March 5, a woman in her 70s with underlying health conditions became the first person in the UK to die after a positive COVID-19 test.

The Prime Minister’s official spokesman said the virus was “very likely to spread in a significant way”, and Professor Chris Whitty, the Government’s chief medical adviser, told MPs that the UK has moved from keeping the virus out to its ‘delay’ policy.

However, that week also marked an important milestone in the fight against COVID-19, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson announcing £ 46 million in funding for vaccine research and rapid diagnostic tests.

Road to lock down

On 12 March, the chief medical officers of the four UK nations raised the risk to the UK from moderate to high. It was too late for the thousands of racers attending the 4-day Cheltenham Festival in which 68,500 horse racing enthusiasts were on their way to see the Gold Cup on March 13th.

Two days earlier, 54,000 football fans had flocked to Anfield to check on the Liverpool Champions League tie against Atlético Madrid. There were 3000 fans away that day who had traveled from a Spanish city that had already become a major virus hotspot.

By the middle of the month with pandemic deaths reaching 55 and the number of cases exceeding 1500, the UK had slipped towards its first lock.

Most pupils have been told schools will close from Friday 20 March, and exams have been postponed.

The following week, Boris Johnson spoke to the country on TV. “I have to give the people of Britain a very simple direction – you have to stay at home,” he said.

All non-essential shops, libraries, places of worship, playgrounds and outdoor gyms were closed, and police were given powers to enforce the measures.

England’s Health Secretary Matt Hancock has announced plans to open a temporary hospital, NHS Nightingale Hospital at the ExCeL in London, to add additional emergency care capacity.

The first two NHS doctors working with COVID-19 died on the same day: one GP and the other a surgeon.

At 8pm, March 26, millions of people will take part in the first ‘clap for carers’ obedience to the NHS and care staff.

In response to growing dissatisfaction among health workers over the lack of personal protective equipment, Home Secretary Priti Patel told a briefing on Downing Street on April 11 that she was “sorry if people feels that there is a failure ”.

On the same day, about 58% of capacity was in emergency care beds in England.

In April, the UK caused 10,000 deaths, and Matt Hancock set a target of 100,000 COVID-19 tests per day.

Summer stop

By July, the Government was confident enough to release locking restrictions, with pubs, cinemas and restaurants allowed to reopen from the 4th.

By August, we were eating out to help as the economy struggled back to its feet.

In September, more than a million people downloaded a contract search app for England and Wales on the first day of release.

On 14 October, England moved to a three – tier system in which areas were classified according to their disease levels and according to various restrictions. The Liverpool City area was among those who entered stage 3. The relationship between the Government and another tier 3 city, Manchester, was tense.

People in other areas had more freedom, especially in the south of the country.

The second lock

As we moved into the autumn, Wales chose ‘fire-breaking’ locking.

By the end of October, the Prime Minister had abandoned his desire to block a second national closure.

On Halloween, Mr Johnson apologized to TV “for disturbing your Saturday afternoon” when he announced a 4-week lockdown against a “massive abstract growth in the number of patients ”, and the risk of“ forcing doctors and nurses to choose which patients should be treated ”.

Pubs, restaurants and non-essential shops close again.

The restrictions would end on Dec. 2, Mr. Johnson promised.

However, Christmas would be “very different this year”, he said.

Plans for a Christmas break with SARS-CoV-2, where families would be able to meet for four days of receptions, have been postponed to just one day.

Concerns were raised when a weekly infectious study by the Office for National Statistics in England on 24 December showed that the incidence of COVID-19 in secondary school children aged 11 to 16 had risen.

UK hospitals and emergency services were coming under increasing pressure.

happy New Year

Despite a new strain of SARS-CoV-2, known as the UK or Kent variant, which has been found to be more contagious, new national locking measures for England have been announced from January 4, 2021.

On 21 January, the quarantine government declared a mandatory hotel for people traveling to the UK from a list of high-risk countries.

The Cavalry Over the Hill

Behind the scenes, there has been a major international effort to develop vaccines that would bring the world back from disease, death, social isolation, and economic hardship.

Sharing the SARS-CoV-2 genetic code allowed scientists to work on developing vaccines that target the virus’s spike proteins to protect people from developing COVID-19 , which could hinder transmission.

Some, like the Oxford group, followed the vectored adenovirus approach; others a newer messenger RNA (mRNA) platform.

On December 8, 2020, Margaret Keenan became the first person in the world to receive the vaccine in a community setting with the vaccine developed by BioNTech in collaboration with Pfizer.

Before she turned 91, she described it as “the best early birthday gift I could ever want”.

Following an emergency approval for the Pfizer vaccine by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, vaccinations from AstraZeneca / Oxford and Moderna were approved.

To date, vaccination calls have been issued to people aged 56 and over.

Currently, 23.3 million people in the UK have received the first dose of vaccine, and 1.4 million the second dose.

Schools have reopened for face-to-face tuition, and the Government has set out a ‘roadmap’ for spreading restrictions in the spring and summer.

However, in the last 7 days, 1082 people in the UK have died within 28 days of a positive COVID-19 test.

And scientists have warned that the impact on transmission has not yet allowed more people to be evaluated.