Whether or not a person with COVID-19 develops a serious infection depends largely on how their immune system responds to the coronavirus.

But scientists still don’t know why some people get a serious disease while others only have mild symptoms – or no symptoms at all. Now, a new study from Yale University is shedding light on the issue.

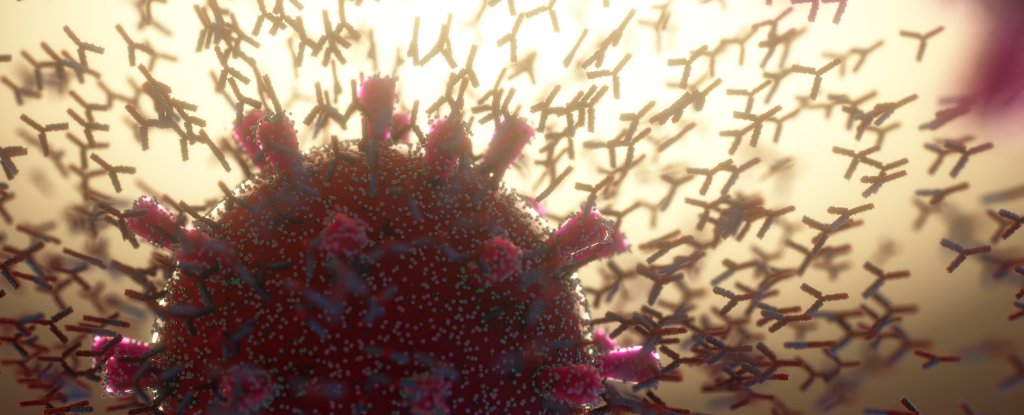

The research, which has not yet been peer-reviewed and published in a journal, suggests that in patients with severe COVID, the body produces “autoantibodies”. These are antibodies that – instead of attacking the invading virus – attack the patient’s own immune system and organs.

The researchers found that people with severe COVID had autoantibodies that migrated to vital proteins involved in the identification, warning and cleansing of cells called the coronavirus.

These proteins contain cytokines and chemokines – important messengers in the immune system. This disrupted the normal functioning of the immune system, inhibiting antiviral immunity, which could exacerbate the disease.

Connections with self-defense disorder

For many years, autoantibodies have been known to be involved in autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

It is not known why some people develop these antibodies, but it appears to be a combination of genetics and environment. Viral infections have also been linked to the onset of some autoimmune diseases.

Earlier this year, scientists reported that patients who had no history of autoimmune disease developed autoantibodies after receiving COVID. In these studies, the autoantibodies were found to identify targets similar to those found in other well-known autoimmune diseases, such as proteins commonly found in cell membranes.

Later studies found that people with high COVID can also develop autoantibodies to interferons, immune proteins that are heavily involved in fighting viral infections.

The Yale scientists who conducted the latest study used a new device designed for autoantibodies that work against thousands of body proteins. They searched for autoantibodies in 170 hospitalized patients and compared them with autoantibodies found in people with moderate or asymptomatic illness, as well as people who were not infected with the virus.

In the blood of hospitalized patients, they found autoantibodies that could attack interferons, as well as autoantibodies that could block other vital cells of the immune system such as natural killer cells and stem cells. T.

The findings showed that autoantibodies were very common in critically ill COVID patients.

Yale researchers conducted further experiments in mice, which showed that the presence of these autoantibodies could exacerbate the disease, suggesting that these autoantibodies may contribute to the severity of COVID in humans.

Not the whole story

Although COVID patients had many autoantibodies that targeted immune system proteins, the researchers did not find specific COVID autoantibodies that could be used to differentiate severely ill COVID patients.

What determines whether a person is going to suffer from severe COVID depends on many things, and autoantibodies are not the whole story.

But the research suggests that people with pre-existing autoantibodies may be at greater risk of getting severe COVID. These individuals may have deficiencies in their immune response during early coronavirus infection or may be prone to the production of novel autoantibodies that may impair their immune response to the virus.

Researchers are increasingly focusing on the link between poor COVID and incorrect immune responses that target healthy bones and proteins in the body. The presence of autoantibodies suggests that, for some patients, COVID may be a coronavirus-induced autoimmune disease.

Understanding the drivers of autoantibodies production will help scientists develop new treatments for this disease.

Scientists do not know how long these autoantibodies last after the disease has cleared. An important unanswered question is whether long-term damage caused by autoantibodies could explain some long-term COVID symptoms.![]()

Rebecca Aicheler, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Cardiff Metropolitan University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.