The world is awakened in Covid-19 data. Has this information helped?

A new study looks at how six different maps affected public knowledge, risk perception, and behavioral intentions show the incidence of Covid-19 in the U.S. on May 11, 2020.

An upshot.

Data on the number and distribution of Covid-19 cases as a whole had little effect. In fact, respondents in a control group, for whom no data were provided, performed better on a knowledge test of the current state of epilepsy than respondents provided data.

The idea for this study was brilliant, taking advantage of several data images provided by a range of reliable sources at a time when the public was showing great interest.

The maps.

To measure the association of different ways of viewing spatial data with observer experience, risk perceptions, and behavioral intentions, researchers selected six different maps that varied according to their characteristics. Some reported data at the state level and others at the county level.

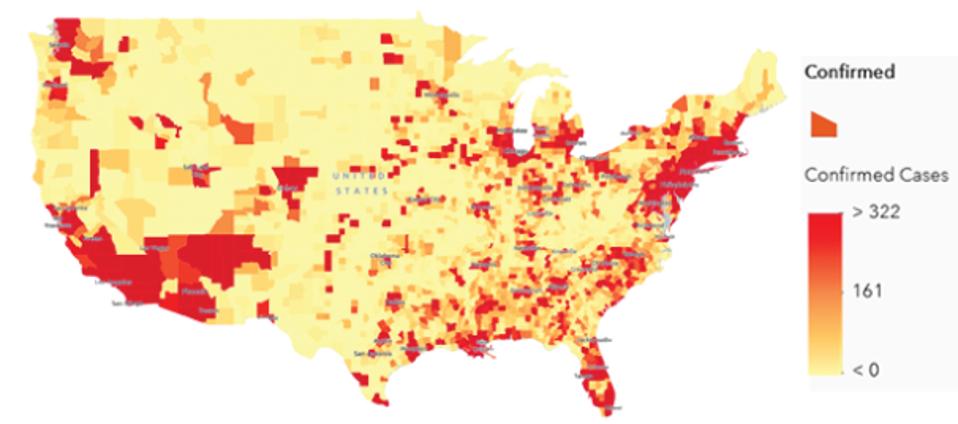

A map made by researchers at Johns Hopkins University shows the frequency of Covid-19 in the USA … [+]

Adapted from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2774639.

Some used “bubbles” to show the extent of epilepsy, while others used a color gradient called a “heat map”.

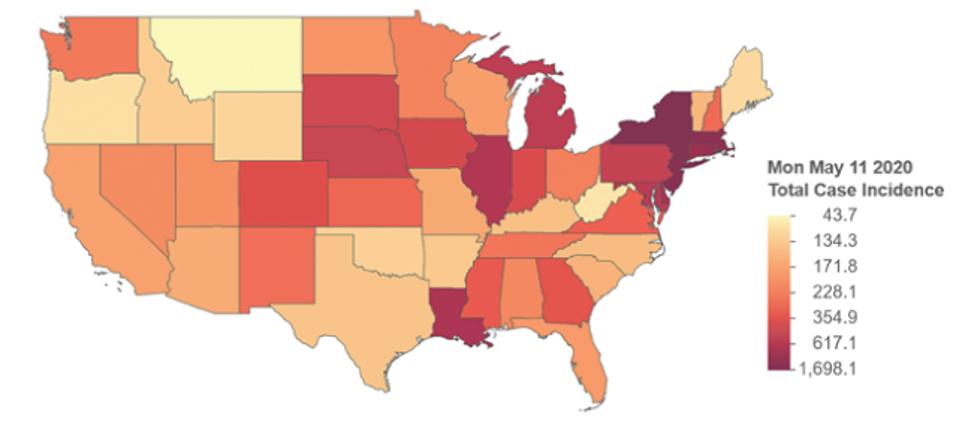

A map produced by the Kaiser Family Foundation shows the frequency of Covid-19 in the US using a … [+]

Adapted from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2774639.

Finally, some maps were expressed in terms of the total number of cases and others as the number of cases per person.

A map made by researchers at the University of California Davis shows the frequency of Covid-19 … [+]

Adapted from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2774639.

Survey respondents were provided with just one of these maps and tested their knowledge of the total number of cases and issues of each individual, an understanding of individual and social risk, and intentions to adhere to guidelines. Covid-19.

The Results.

Frequency maps (per capita cases) were poorly translated into overall case knowledge. Knowledge of the total number of cases was greater among respondents who had seen maps showing the total cases than per capita cases. This is not surprising. What is surprising is how great the difference was.

Some maps have greatly improved knowledge about frequency:

- Heat maps (also known as choropleths) works better than bubble maps. This is interesting because coropleths tend to emphasize the importance of cities versus rural areas. It is difficult to see small areas with a high frequency on the map.

- State level maps work better than county level maps. This is probably due to the fact that there are fewer states than counties. To understand the whole it is necessary to “put up” the different states, or engage in another mental process that is close to sum. Of course, this is easier to do with 48 states on display compared to 3,108 county-by-county equivalents. (Alaska and Hawaii are excluded from the maps.) This is particularly interesting because the county’s data is more accurate, at least in the sense that they describe the counties in more detail. -places where things are congested. (So the usual advice about using the smallest area units for coropleths may not be the right advice in this case. State level maps in this case may override the disadvantages of coropleths in small areas such as urban counties.)

- Per capita maps work better than whole case maps. (Not surprising.)

Looking at maps of any kind did not affect individual risk perceptions. There was no evidence that data presentation, or even data presentation itself, had any impact on individual risk perception. This is sad. Since there was nothing wrong with the data itself (but see more about this below), the reason is that something needs to be thoroughly researched.

By looking at maps the audience was a little more optimistic about social risk. Understanding social risk – measured in terms of hope or pessimism that an accidental situation would improve within two weeks – was weakly influenced by showing a map. What kind of map didn’t matter. Interestingly, respondents who viewed a map were more optimistic than respondents who did not provide any data.

Looking at maps had no effect on behavior. There was no evidence that data had any effect on intent to comply with protective guidelines.

Looking at maps provided a less accurate knowledge of the whole issue than no information at all.

These results are remarkable. In particular, they suggest that access to information of a widely distributed type in the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic had almost no effect on public understanding of the disease. Even more astonishing is the inconvenient result that getting data was sometimes worse than not getting data at all.

What does this explain and does it matter?

The definition.

The last particularly remarkable discovery was that maps seemed to result from a reduction in knowledge. My view is that this is not a general pattern, but a result of the design of the study. We know from details reported in the survey (first key finding above) that respondents provided maps of tricead (ie maps of the number of cases per person) answered questions about total number of cases worse than those with maps showing the total number of cases. This makes sense. Even if you understand correctly what information is displayed in frequency maps, if you do not know where the population is dense (either because you know enough on U.S. geography or because there are also population size maps), there is no way to determine the total number of cases. One might even assume that the information is presented by frequency maps destructive to knowledge of whole issues, because it is false, because it is a measure of something very different.

Therefore, respondents with frequency maps are expected to show less knowledge of overall issues. These frequency maps included two of the six maps displayed. Thus, about a third of the respondents who received maps were given damaging information. If the difference between no information (no map displayed) and good information (map of total number of cases) is small, the difference between the group without information is expected (no map displayed) ) and would be a group with corrupt information (two-thirds with good information and one-third with destructive information), gradually, but negatively. This is, of course, what the researchers found.

What did we learn?

First, raw data were of less value than the average respondent. Second, scientists, data journalists, bloggers, and others who store and present data to the public should be aware that there are visual consequences to the way data is stored. display (e.g. heat maps vs bubble maps). Lastly, and most importantly, there is still much opportunity to develop a common knowledge of how to interpret quantitative data and information, and how to design the best images. The gaps between those with and without access to data – in terms of knowledge, understanding of risk, and intention to behave – were small. But they should be big. Data should be informative, especially in terms of conditions, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, where there is a lot of confusion and uncertainty. In a society that relies heavily on data to make important decisions, it is essential that the public be informed about the interpretation of graphs and figures.