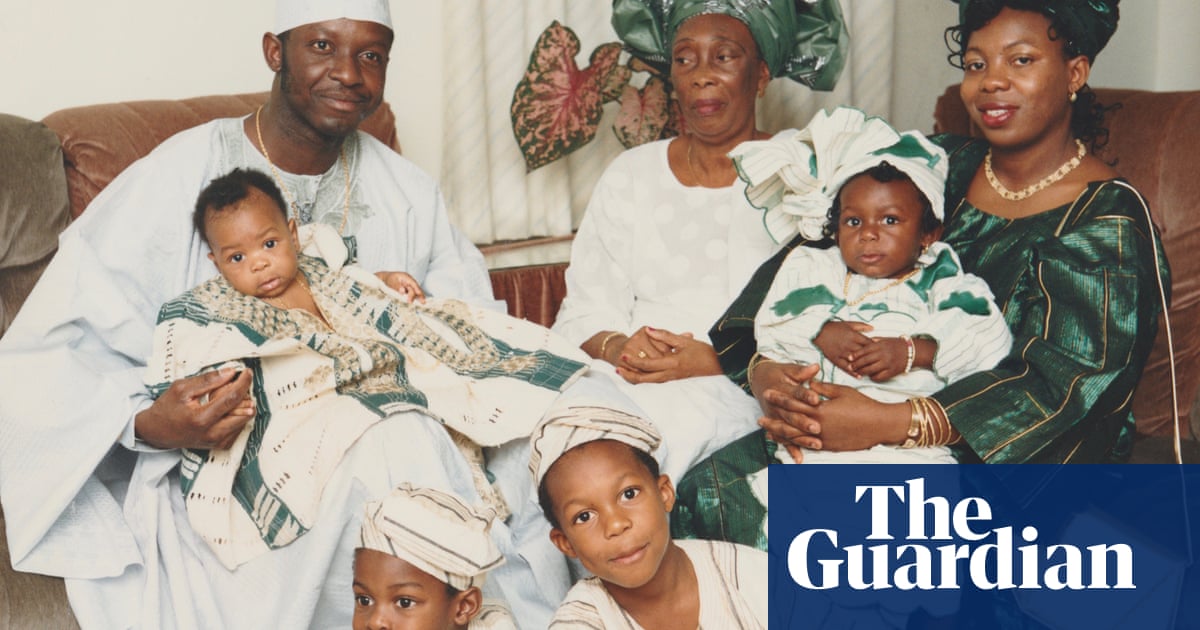

Gabriel Moses would regularly go through his family photo records as he grew up in south London. Shot by a local photographer, the images are simple images captured by his Nigerian family at their home in Catford.

“You can see that there is a lot of personality in the images,” he says. “You can feel that there is a lot of energy and for me now as a designer that is what I want to achieve for my generation. “

For Moses and a group of young black photographers, the family photo album has grown into a creative creative tool. Moses, Swedish-Somali artist Ikram Abdulkadir, Nigerian photographer Isabel Okoro and Ethiopian-American filmmaker and illustrator Dawit NM have all looked into their old records for inspiration.

The idea of representation is at its heart. Moses says the reason he picked up a camera was to document life in south London as he knew it. Dawit wanted to counter the popular image of Ethiopians and Abdulkadir wanted to do the same for Somalis in Sweden.

“Like Ethiopia when I moved to America one thing that stood out was the lack of proper representation of Ethiopia,” says Dawit. “My aim as a photographer was to contradict that statement. “

-

‘Collage I made for my picture book, Don’t Make Me Look Like the Kids on TV (self-publishing, 2018). The stamps were from letters my mother received from Ethiopia after she moved to the United States. ‘- Dawit NM

-

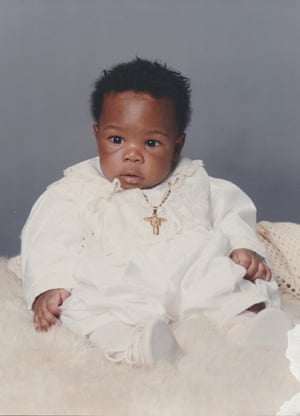

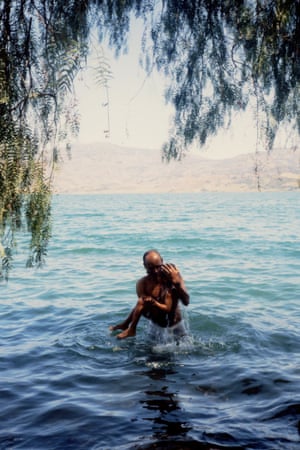

‘My mother, heavy with me, Ethiopia.’ Right: ‘My father, carrying me out of the water, Ethiopia’ – Dawit NM

“I’m trying to take pictures of what I see – this is not the image that the mainstream association of Somali people in Sweden might have,” Abdulkadir says.

Abdulkadir’s images are often of friends, family and – especially – his younger sister. They may not be set up in the same way as a typical family photo, but their simplicity is inspired by them. “There are many family records belonging to Somali families here in Sweden from their early years in Sweden,” she says. “It’s interesting to see the styles of clothing they wore – people would take a lot of pictures in the snow.”

Abdulkadir’s family moved to Sweden when she was two years old, to follow her grandfather, who had already moved there, while Dawit came to Maryland with his family at the age of six.

For each, photographs and sketches were a way of connecting with their history and cultures. “Family photography has a function; there’s a reason you take them whether it’s to invest in your family, their culture, or their way of life, ”says Dawit, who published a book called Don’t Make Me Look Like the Kids on TV in 2018.

For Abdulkadir there was another action. “A lot of it is a reason to send your family back home to reassure them that you are doing very well,” she said.

Moses says that the work of Malick Sidibé – the Malian illustrator best known for his studio paintings – was inspiring, with the idea of production and how people choose to present themselves being a key part of his work. “His images reminded me of the pictures my mother showed me when she was very young and the pictures my grandmother would take on them,” he said.

Okoro’s mother also influenced her. At lockdown she started sharing photos from her childhood with Okoro. “When I was a child she loved to get pictures and always spent time in the studio. I feel like it’s a completely different reason why I started taking pictures. ”

Dawit has a strict rule: he only takes pictures of family, friends or people he knows. If he takes an image of someone who is not inside his circle, he hides his face. The cause is rooted in an attempt to defy classical western images of Africa. “A lot of the pictures come from Africa where photographers go there, and they may not ask permission,” he said.

Abdulkadir is also aware of the types of images she makes. “I don’t really follow the kind of trauma porn, where you just show black people in pain all the time,” she says.

Dawit hopes that a new generation of people in the diaspora will follow the family record tradition, even with the advent of Instagram. “I wish people would invest more time in their family photos,” he says. “By doing that they can build a small community and inspire others to do the same. ”