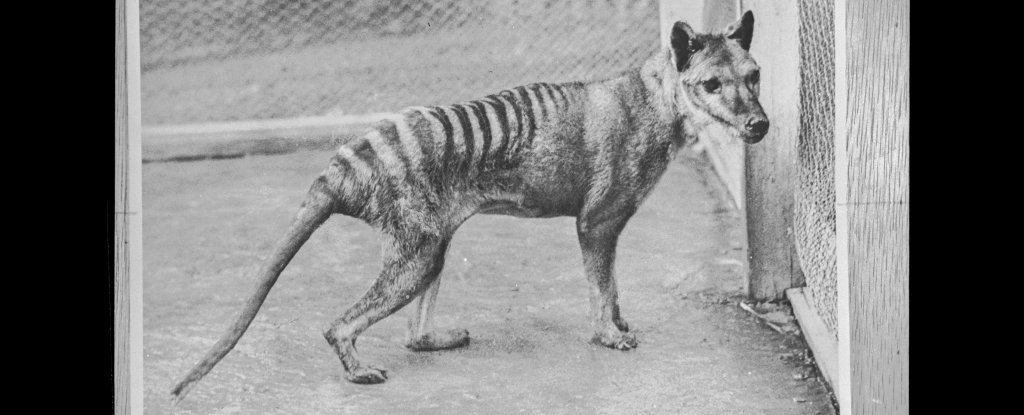

Thylacine has long been considered a truly amazing species. The extinct Australian beast was a merchant, but his skull was bright in appearance, almost identical to that of a fox and gray wolves.

Now, new research has shown that this appearance was not limited to adult thylacines (Tholacinus cynocephalus) – was present even in the skulls of newborn pups, and persisted throughout the life of the animal.

The discovery could shed more light on how different animals can use similar features to use similar ecological areas, even though they may be unconnected and separated by space and time – something called convergent evolution.

“Surprisingly,” said biologist Andrew Pask of the University of Melbourne in Australia, “the Tasmanian tiger pups were more like wolf pups than other closely related marsupials.”

Although thylacine – commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger – was extinct by humans in 1936, its remains are housed in museum collections. In collaboration with Australian museums, the researchers donated several thylacine skulls at different stages of life and sizes – from newborn to adult – to X-ray CT scans.

These have been compared to other marsupial skulls from Australian museums, including those of the fort (Sminthopsis), recently discovered as one of the closest genetic relatives of thylacine, and the eastern quoll (Dasyurus viverrinus), another carnivorous marsup of the same order as the thylacine.

From the Northern Museum in Alaska, the team also borrowed and CT scanned a skull from the gray wolf (Canis lupus), again at different stages of life and sizes from newborn to adult, to compare with thylacine skulls. The last common ancestry between the two species was 160 million years ago.

Thylacine skull (left) and wolf (right). (The Pask Lab)

Thylacine skull (left) and wolf (right). (The Pask Lab)

“We know that thylacine and the wolf look like adults, but we don’t know when they started to show similarities in development,” explained biologist Axel Newton. from Monash University in Australia.

He and his team recently rebuilt the development of a pouch of thylacine puppies. That research added to this comparison as well, allowing the team to look for similarities between thylacines and marsupials or other wolves at the earliest stages of life.

A recent study by a team that included Pask and Newton found that wolf-like genes and thylacines regulate their craniofacial development. The new research, comparing the skulls of the two animals, supports this. From birth to adulthood, the skulls of both animals were not only similar to each other, but followed a similar growth pattern.

Previous research has suggested that the way marsupials are born – developing in a bag, rather than in a space – limits the diversity of skulls. This new study shows that not only can convergent evolution occur in animals that are otherwise anatomically different, but that marsupials can develop skulls that are completely different. from each other.

And the comparison between the two species is a remarkable example that can be used to study convergent evolution in general.

“By comparing total growth cycles from newborns to adults,” said biologist and palaeontologist Christy Hipsley from the Victoria Museum and the University of Melbourne in Australia, “we were able to see small differences in development. indicates when and where in the skull changes to meat-eating. cell level rise. “

Homogeneous evolution like this is a powerful reminder of just how the environment has shaped our anatomy and physiology over hundreds of thousands of years of evolution. Every animal, including ourselves, is deeply connected to our world.

The research was published in Communication Biology.