Ewa Bazan, archivist at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, compares her work on accessible records to compiling a “puzzle” featuring new names and stories about camp residents. the death of the Nazis.

Ninety percent of the camp’s famous files were destroyed by their guards before fleeing but a recently concluded two-year collaboration with the Arolsen Archives in Germany reveals new information.

5 צפייה בגלריה

The entrance to Auschwitz-Birkenau

(Photo: AP)

“We didn’t know what to expect when we started the project,” Bazan told AFP, barely hiding her feelings.

The patient, humble study conducted by Bazan and her colleagues has revealed the previous identities of about 4,000 camp residents as well as information about 26,000 others.

Currently, about 300,000 out of the 400,000 residents held at the camp are known for their identities.

Names found by Bazan and her team include the names of French fighter and painter Leon Delarbre or Polish artist Franciszek Jazwiecki, whose cold paintings of prisoners can be seen in a museum champa.

Both painters were transferred at some point from Auschwitz to Buchenwald and it is in the records of that camp, which are preserved in the Arolsen Archives, that new information about them has been found.

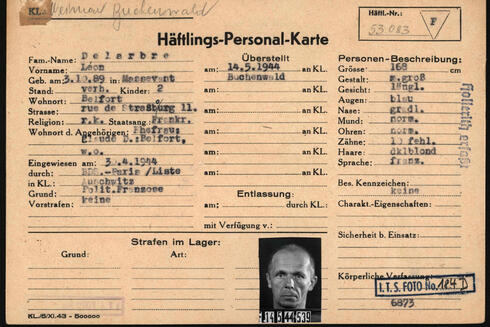

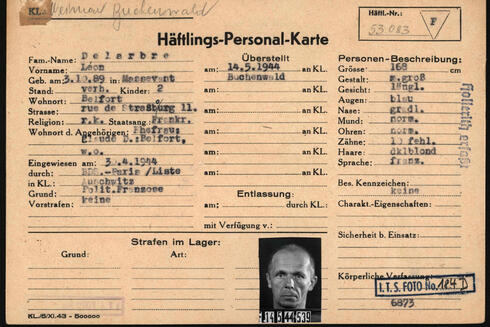

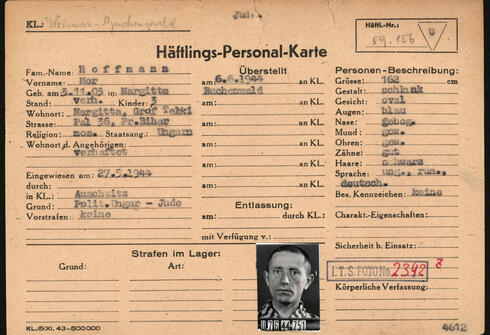

5 צפייה בגלריה

This reproduction shows a prisoner card (Haeftlings-Personal-Karte) of the Frenchman Leon Delarbre held prison by the Nazis in the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

(Photo: AFP)

Delarbre’s file includes a photograph, his address in the French city of Belfort, his date of birth, a description of his appearance including the missing teeth and the head. moved between the camps.

Delarbre and Jazwiecki survived the camps but the latter died of tuberculosis a year after their liberation.

Krzysztof Antonczyk, head of the museum’s digital archive, said in addition to the camp’s inmates, another 905,000 people were abducted and evacuated upon arrival, leaving no records.

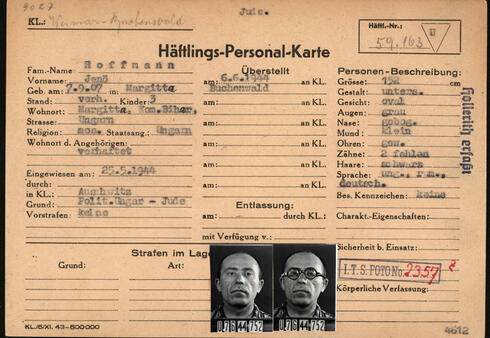

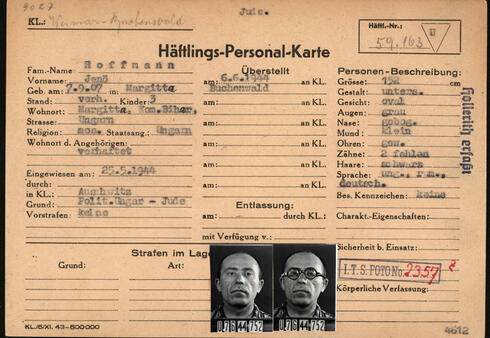

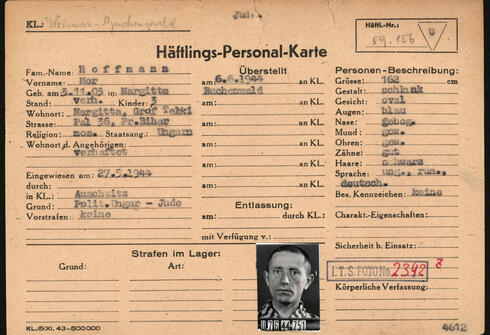

5 צפייה בגלריה

This reproduction shows a prisoner card (Haeftlings-Personal-Karte) of Hungarian Jeno Hoffmann who was held in prison by the Nazis in the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

(Photo: AFP)

“Their names sometimes only appear on transport documents used by the Nazis,” he said.

The Arolsen Archive contains approximately 30 million documents, including the archives of the SS and Gestapo and records from the concentration camps.

Over the years, they have provided information to the families of ex – prisoners and have not been opened for academic research since 2007.

The files can provide unexpected information.

A single record sometimes contains details of all the members of a prisoner’s family – their names and ages and an indication of whether they were also held at Auschwitz or another camp, if they died or were evacuated.

“By one name, we can find out things about other people we didn’t know that were held at Auschwitz,” Bazan said.

5 צפייה בגלריה

This reproduction shows the card of the Hungarian prisoner Mor Hoffmann who was imprisoned by the Nazis in the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

(Photo: AFP)

A total of 120,000 documents relating to Auschwitz prisoners were digitized as part of the project.

Among the finds were many records of Hungarian people who were transported to Auschwitz after May 1944 and whose names do not appear in any other archive.

Two of them, brothers Jeno and Mor Hoffmann, were evacuated from Auschwitz to Buchenwald and back.

Their files contain the names of their parents and wives, all of whom were also prisoners.

“Auschwitz is the largest cemetery in the world without any graves,” Antonczyk said, comparing the digital archive that is expanding into a “kind of epitaph” for the victims.

“We want to establish the identity of as many prisoners as possible,” he said.

5 צפייה בגלריה

Survivors of Nazi death camp Auschwitz arrive for a memorial service on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Poland

(Photo: AP)

Using databases and digital technology, researchers can now trace the routes taken by prisoners across Europe while being transported around Nazi camps.

Bazan, who has worked at the museum for 20 years, said the project was a “heartfelt desire” to respond to the thousands of families who contact the museum each year for information. about their favorite people.

“When someone comes to see us hoping to find out something about their relatives and we can’t help them it’s sad too.

“The smallest detail is important to relatives,” she said, regretting that some names are “lost forever”.