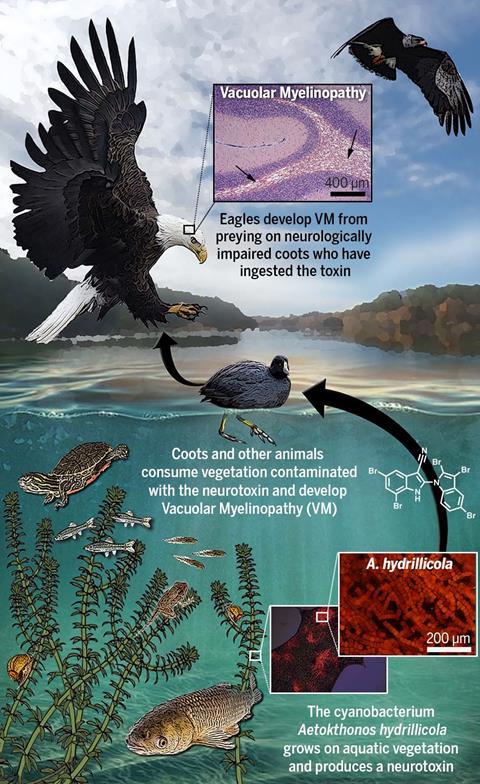

Chemical forensic work has solved a decades-old mystery of why bald eagles and other U.S. wildlife have died of severe neurodegenerative disease. The scientists have determined that the culprit is a neurotoxin product with cynanobacteria that grows on invasive aquatic plants.

Study co-author Susan Wilde, a water scientist at the University of Georgia, he identified the previously unknown cyanobacterium that appeared to be causing the disease known as avian vacuolar myelinopathy (AVM) on leaves Hydrilla verticillata in 2005. She named the bacterium Aetokthonos hydrillicola – ‘kill an eagle that grows on it Hydrilla‘. At least 130 bald eagles have died since AVM was discovered in 1994, and the figure covers only the recovered and properly tested birds, so the number of higher deaths.

Timo Niedermeyer, now a natural product chemist at the University of Halle-Wittenberg in Germany, co-director of the paper with Wilde, first analyzed Wilde samples in 2013 while working at the University of Tübingen. It took about 18 months to culture the bacterium, but the tests came back negative – there was no poison. “It turned out that the pressure we were cultivating didn’t produce any poison, and that was a big disappointment,” Niedermeyer recalls. ‘Then we played with cultivation conditions and we were still unable to get the cyanobacteria to produce the toxin.’

The breakup did not occur until he moved to Halle-Wittenberg University in 2017. After Wilde further samples of Hydrilla from a lake where the AVM revolution took place, experiments in Niedermeyer ‘s new laboratory using a more sensitive image spectrometer found new material that is only produced on the leaves where the cyanobacteria grow, but which are not. extracted by culture bacteria.

‘Very surprising’

Further study showed the presence of brominated molecules. Hydrilla accumulates bromide from water, thus supporting toxin formation by creating an environment rich in bromide. ‘It was very surprising to see that the production of this toxin is largely dependent on bromide, which is not usually found in high concentrations in freshwater,’ says Niedermeyer. World of Chemistry. That was the eureka time, and then we added bromide into the middle and the cyanobacteria started to remove the toxin that is seen in the leaves from the lake. ‘

The fertilizer – named aetokthonotoxin, which means ‘poison that kills the eagle’ – was then shown to stimulate AVM. ‘We now know who killed them, the cyanobacteria, and we know its weapon, the toxin, but now we need to find out where the bromide comes from, and the molecular mechanism of the toxins this, ‘says Niedermeyer. AVM causes brain injuries and is highly toxic not only to eagles, but to other birds, fish, turtles, nematodes and more. It is not known whether the poison represents a threat to mammals.

Hans Paerl, a professor of environmental sciences at the University of North Carolina’s institute of marine sciences who was not involved in the study, says this international team produced ‘some very good biochemistry’ which highlights -the complexity of these fertilizers and their toxins.

Tip of the iceberg

Paerl points out that the findings are consistent with the Botswanan government’s September 2020 decisions that the deaths of hundreds of elephants were likely to be caused by cyanobacterial neurotoxins, in addition to a 1996 report from Brazil of more on 70 people die as a result of contaminated water cyanobacteria.

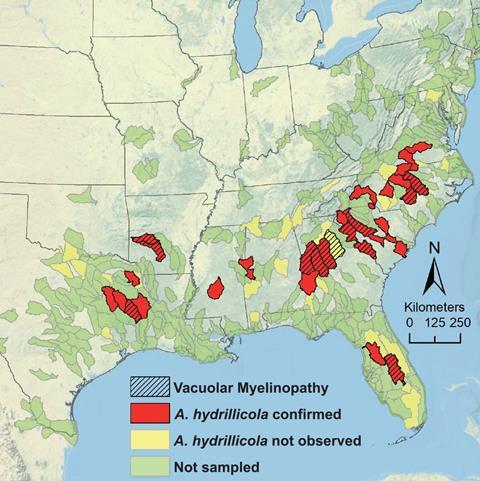

‘We’re just seeing the tip of the iceberg,’ he warns. ‘I think we will see more of these links between extracted secondary metabolites that directly affect organisms from plants to mammals. ‘It confirms that Aetokthonos hydrillicola there are special cells that can regulate atmospheric nitrogen. ‘Organisms like the one described are likely to grow in different places if they get a foothold because they are not limited by the availability of nitrogen,’ he explains.

Greg Boyer, a chemist at New York State University, is concerned. ”Hydrilla verticillata a very aggressive genre here in New York state in the Finger Lakes, ‘he says. ‘There’s a big eagle crowd up here, and if the Hydrilla verticillata spreads and if the cyanobacteria come with it, it could be quite destructive up here – it has the potential to be very ugly. ‘