I.is there still hope? You would always think so, looking at the work of Mexico-born artist Aliza Nisenbaum. Renowned for her vibrant and intimate portraits of watched communities, she has spent her career making the fringe visible. Her new exhibition at Tate Liverpool pays homage to the Merseyside healthcare staff, who painted it remotely, dividing it into two large group photos and 11 individual ones. This is the result of extended video calls by 26 hospital staff, including student nurses, a pulmonologist and a porter.

“It’s a big job to do justice to my seats,” Nisenbaum tells me of Zoom’s call from her temporary studio in Los Angeles, where she spent most of the year (as she usually lives in New York). “But in this case even more, because they’re putting their lives on the line.” This new commission is on display alongside existing works, including another group photo – of tube workers made during Nisenbaum’s residence at Brixton underground station in 2019.

She was born in Mexico City to a Russian Jewish father and a Norse-American mother. Rising up, when she visits her grandparents near the city center, she remembers capturing scenes from the 1960s social-realist painter David Alfaro Siqueiros, March of Humanity, which is believed to be the wall largest in the world. She once again took a similar interest in María Izquierdo ‘s dreamy, sad paintings, which in 1930 became the first Mexican woman to be exhibited in the USA.

“My job is between the private and public poles,” she says. Her sister Karin, now a distinguished professor of philosophy, first introduced her to the French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas. He believed that face-to-face meeting was at the heart of human compassion. “In front of my face,” he wrote in 1963, “I always want more of myself.”

These words, which have added meaning in a time of masks and loneliness, inspired Nisenbaum to force herself to introduce some of humanity to a sacrosanct tradition of images. She gained international prominence when her domestic paintings of Latin American immigrants – whom she taught English at artist Tania Bruguera’s community center in New York – showed off the walls of the 2017 Whitney Biennial in the city.

For her first major solo exhibition in the UK, the 43-year-old artist was planning to live at the Sefton Park lot gardens in Liverpool. But as the pandemic and travel obstacles came, she turned her attention to those on the front line, making an open call, then choosing a diverse group of seats from three hospitals there. the Merseyside (participants received a flat tax and hospital trusts will receive 10% of future work sales).

In addition to a dozen individual candidates, the artist selected a group application from the emergency department at Alder Hey children’s hospital, which also treated adults at the height of the pandemic. “I was like, ‘I can’t No do this’, right? “she says.

The staff is now immortalized over two large canvases with a clear pattern, the largest of which is nearly four meters wide. They are represented in scratches of all shapes and colors, including a hazmat suit, sitting on the wooden plants and undulating benches that enjoy the hospital grounds. Rows and depths hardly add up, giving the works a different quality.

aliza

While colleagues were painted separately, based on photos taken at their homes, the team spirit is evident: they look at each other, smile, almost smile. to speak. Some can be seen holding sheets of paper covered in doodles. These come from therapeutic exercises of all kinds, in which Nisenbaum – who studied psychology in the late 1990s before moving to the School of the Chicago Institute of Art – asked her subjects to draw a picture of her. reflect their own knowledge, which they would discuss.

“This was special,” says Lalith Wijedoru, a pediatric consultant who appears in one group. “It really showed the artist wanting to know her subject and represent her. ”

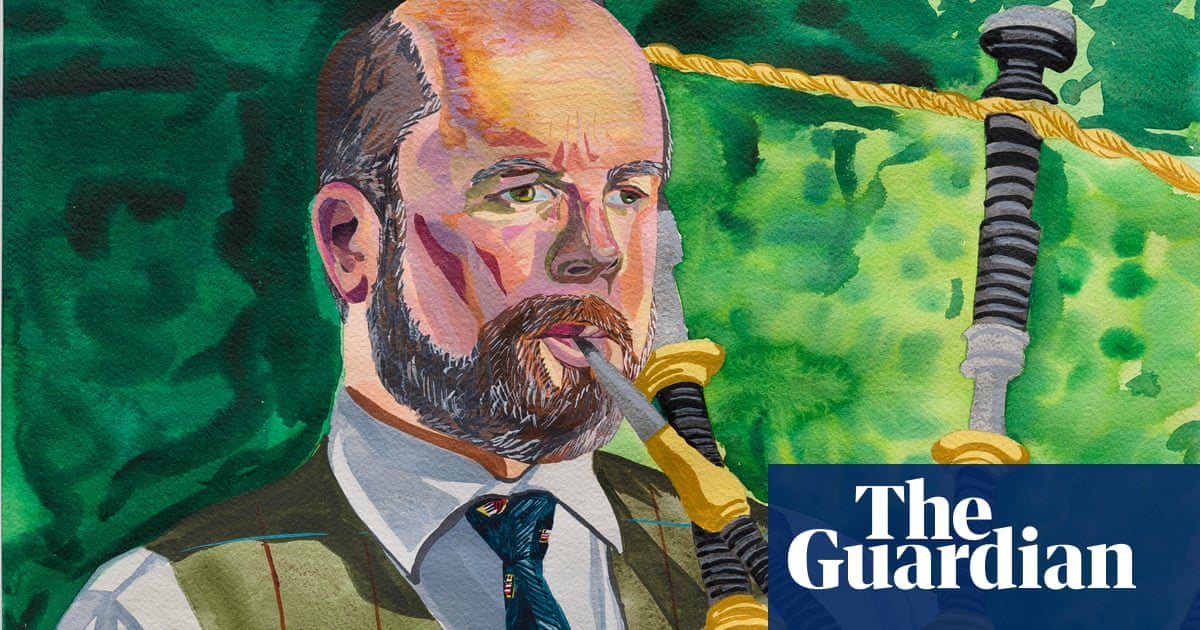

Along with the large canvases are individual watercolor paintings. They feature a student nurse lying in bed reading, a chaplain standing hard with stained glass windows and a professor of medicine blowing pipes loudly in his garden. They are packed with half a dozen still luxurious flowers, ranging from cup-shaped California poppies, drooping yellow Daturas, dark fleshy succulents and agapanthus with a drumstick head (one of Claude Monet’s favorites).

They all happened during the artist’s regular trips around LA. It’s a symbolic move towards its occupants, says Nisenbaum: “Like planting flowers for them.”